Put Jimmy Page and Peter Frampton in the same sentence and you get two very different visions of 70s guitar glory. One is the shadowy riff architect of Led Zeppelin, the other the smiling face that turned a talk box into a stadium weapon.

Both shaped how rock guitar sounds, but in radically different ways. If Page built the cathedral, Frampton installed a disco ball in the nave and invited the whole arena to sing along.

Jimmy Page vs Peter Frampton in a nutshell

Page is the darker figure: ex session ace, studio obsessive, master of alternative tunings and layered arrangements. His riffs powered everything from proto metal to mystical folk rock, often in the same song.

Frampton is the crowd charmer: melodic, fluid, almost impossibly tasteful. He made long solos feel like pop hooks and convinced mainstream America to buy a double live album full of extended jams.

So this is not a fair fight in terms of sheer historical weight. Page changed the course of heavy music. Frampton changed what a hit guitar hero could sound like on FM radio. That makes the comparison more interesting, not less.

Roots and rise – studio assassin vs teen prodigy

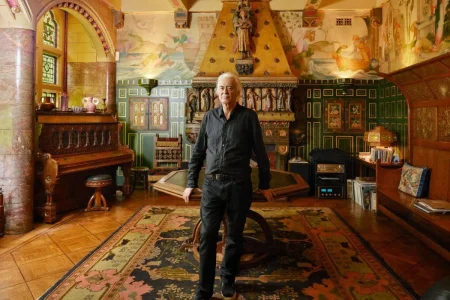

Before Led Zeppelin, Jimmy Page was the secret weapon of London studios, drafted in for sessions with the Kinks and the Who, and already experimenting with bowed guitar, fuzz and unusual tunings. He later described himself primarily as a composer, “orchestrating the guitar like an army” with layered parts rather than just tossing off solos.

When the Yardbirds fell apart, he used that studio brain to design Led Zeppelin as a producer led band. Those early albums sound huge not because of volume alone but because Page stacked acoustics, electrics and overdubs with almost classical discipline.

Peter Frampton took the opposite path. A child prodigy in British pop group the Herd and then co founder of Humble Pie, he was already a pin up and a serious player by his early twenties. After several strong but modest selling solo albums, he finally detonated with the live set “Frampton Comes Alive!“, suddenly recasting him as both guitar hero and poster boy.

How they actually play – riffs vs melodies

Page writes on the guitar the way some people write for orchestra. Listen to “Kashmir” and you hear him using DADGAD tuning to create interlocking riffs that grind against each other rhythmically, with Eastern tinged lines floating over a droning root. It is dense, slightly unstable, and deliberately hypnotic.

Technically, Page is not the cleanest player, and that is part of the appeal. The bends overshoot, the vibrato can be wild, and the timing pushes and drags around John Bonham. The mess is musical: it creates danger, tension and the feeling that the wheels could fly off at any second.

Frampton, by contrast, is about line and phrasing. He came up absorbing Django, Hank Marvin and blues players, then folded that into rock vocabulary. You hear long, vocal like phrases with tidy articulation, intelligent note choice and a lyrical sense of space that keeps even his 70s arena solos from sounding like pure ego.

If Page’s solos feel like spells, Frampton’s feel like conversations. That difference becomes even sharper when the talk box enters the picture and he literally makes the guitar speak.

Gear and tone – Excalibur Les Paul vs the talking guitar

Page and Frampton both built their legends around a single black Les Paul, but they used those instruments in very different ways.

Page’s mythical “Number One” late 50s Les Paul Standard, bought from Joe Walsh in 1969, had a dramatically shaved neck and later wiring tricks that gave him out of phase and coil like textures on top of the classic humbucker roar. It is the sound of “Whole Lotta Love”, “Black Dog” and countless imitated but never matched hard rock tones.

Frampton’s equally famous black 1954 Les Paul Custom, the “Phenix”, became the visual and sonic center of “Frampton Comes Alive” and later survived a plane crash before being returned to him decades later. Where Page chased wiry aggression and harmonic complexity, Frampton dialed in a smoother, vocal midrange that let his melodies sing above the band instead of slicing through it.

Then there is the hardware that defines each player in the public imagination: Page’s double neck SG for “Stairway” and “The Song Remains the Same”, and Frampton’s talk box rig that turned a guitar solo into a quasi sci fi dialogue with the crowd.

| Player | Signature sound | Key gear | Iconic track to study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jimmy Page | Layered riffs, alternate tunings, controlled chaos | “Number One” Les Paul, Danelectro in DADGAD, double neck Gibson | “Kashmir” for tuning and arrangement |

| Peter Frampton | Melodic sustain, vocal phrasing, talk box theatrics | “Phenix” Les Paul Custom, Heil style talk box, classic tube amps | “Do You Feel Like We Do” (live) for phrasing and crowd play |

The talk box vs the riff – two different kinds of showmanship

The talk box vs the riff – two different kinds of showmanship

Frampton did not invent the talk box, but he weaponized it. Given a custom built unit by sound designer Bob Heil in the mid 70s, he locked himself away to learn to literally speak through his guitar, then unleashed it on tour. He has recalled that the first times he used it on “Do You Feel” in 1974, whole audiences lurched forward in shock at this robotic voice asking “Do you feel?” back at them.

That sound became the dramatic centerpiece of “Do You Feel Like We Do” on “Frampton Comes Alive!”, turning an already long jam into 14 minutes of call and response, jokes and wordless noises that felt half rock concert, half stand up set. In a later track by track discussion he admitted that once the talk box arrived, it became the part people waited for and associated with his name more than anything else.

Critics who later mocked 70s excess were often reacting to exactly that kind of moment. Yet there is a reason those solos still work: Frampton’s timing, pitch and sense of melody stay tight even when the gimmick should have worn thin.

Page, in contrast, rarely leaned on effects beyond fuzz, wah and his famous violin bow. His showmanship came from structure. He built entire sets around dynamic arcs, saving monsters like “Kashmir” for the point where the crowd was ready to be flattened. The risk taking came from improvising within those frameworks, not from gadgets.

Live reputations and the punk problem

“Frampton Comes Alive!” did something few guitar heavy records ever managed: it became the biggest selling album of its year and one of the all time best selling live albums, with multi million sales on both sides of the Atlantic. For a while you were not a suburban rock fan unless that double LP was on your shelf.

That success cut both ways. The pop star image, the posters, the soft focus photos and the flood of exposure made Frampton look less dangerous just as punk arrived to declare war on stadium rock. To sneering kids in leather jackets, 14 minute talk box jams were Exhibit A in what needed burning down.

Page suffered some of the same backlash, but Led Zeppelin’s catalogue weathered it better. The sheer heaviness and oddness of tracks like “When the Levee Breaks” or “Kashmir” gave them a darker credibility that punk bands could attack but not easily dismiss. Behind the theatrics there was an experimental streak that fed directly into later metal, post punk and even alternative rock.

Ironically, Frampton has enjoyed one of the more graceful late career arcs of any 70s guitar hero, leaning into blues projects, tasteful instrumental albums and intimate tours, culminating in a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction that finally framed him as more than a punchline about a live album.

So who actually comes out on top?

If you measure by influence on other guitarists, Page wins by a landslide. His riff language and production approach are baked into hard rock, metal and beyond, from tuning experiments to the idea that the guitarist can and should be the studio mastermind.

If you measure by how directly a guitarist connected with mainstream listeners, Frampton has a case that very few virtuosos can match. Millions of non musicians learned to love long solos because of his melodic instincts and that absurd yet effective talking guitar.

The smart move is to steal from both. From Page, learn to:

- Experiment with alternate tunings and let them suggest new riffs.

- Think like an arranger, not just a soloist, when you record.

- Accept a bit of dirt and danger in your phrasing.

From Frampton, learn to:

- Treat solos as singable melodies, not speed contests.

- Use tone and vibrato like a vocalist uses breath and inflection.

- Engage the audience so the guitar feels like part of a conversation.

Put those lessons together and the Page vs Frampton question stops being a contest. It becomes a recipe for a modern guitarist who understands both the power of the riff and the simple, subversive act of making a solo feel like a song.