Rock history loves a good bar-room tale: two titanic drummers, one giant tour, and a surprise onstage swap that supposedly left the crowd slack-jawed. The story goes that in 1977 Keith Moon of The Who stumbled onto a Led Zeppelin stage during the band’s massive North American run and “filled in” for John Bonham, if only for a moment.

It is the kind of legend that feels too perfect to question. But if you care about what actually happened (and you should, because the truth is just as revealing), the Moon-Bonham “switcheroo” sits in the messy middle ground where rock mythology and verifiable fact wrestle for control.

“Moon The Loon” is a nickname that practically dares you to believe the wildest version of any Keith Moon story. But great writing, like great drumming, is about timing and evidence.

Attributed to rock press lore; phrasing varies by retelling

First, the big claim: did Keith Moon actually drum with Led Zeppelin in 1977?

Here’s the honest answer: a fully documented, widely verified Keith Moon sit-in with Led Zeppelin on the 1977 North American Tour is hard to prove using primary-grade sources and consistent setlist documentation. The tour itself is extensively chronicled, and the commonly circulated “Moon replaces Bonham” moment does not appear as a settled, agreed-upon fact in the standard reference trail.

That does not mean Moon and Zeppelin never crossed paths, never jammed, or that the story is “fake.” It means the specific claim needs careful framing: think “famous rumor with fragments of truth” rather than “confirmed historical event with a neat timestamp.”

Why the legend sticks: Moon and Bonham were born for a headline

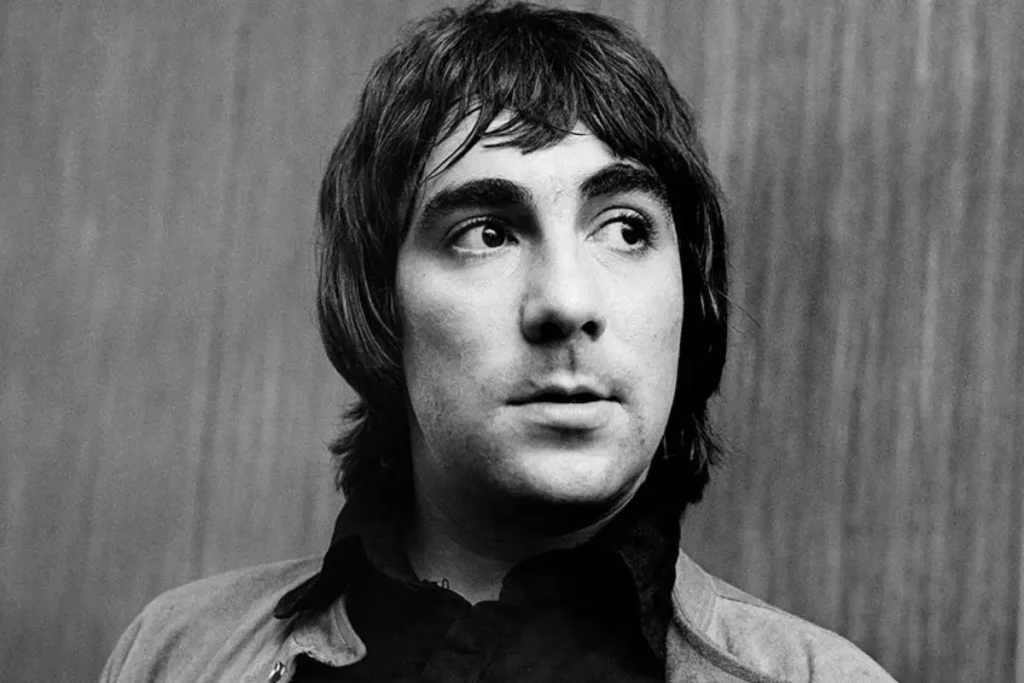

The appeal is obvious if you know the characters. Keith Moon was the human equivalent of a cymbal crash: flamboyant, fast, and allergic to restraint. His approach to timekeeping was less “metronome” and more “controlled demolition,” and that chaos became central to The Who’s identity via his flamboyant, fast, and impulsive style.

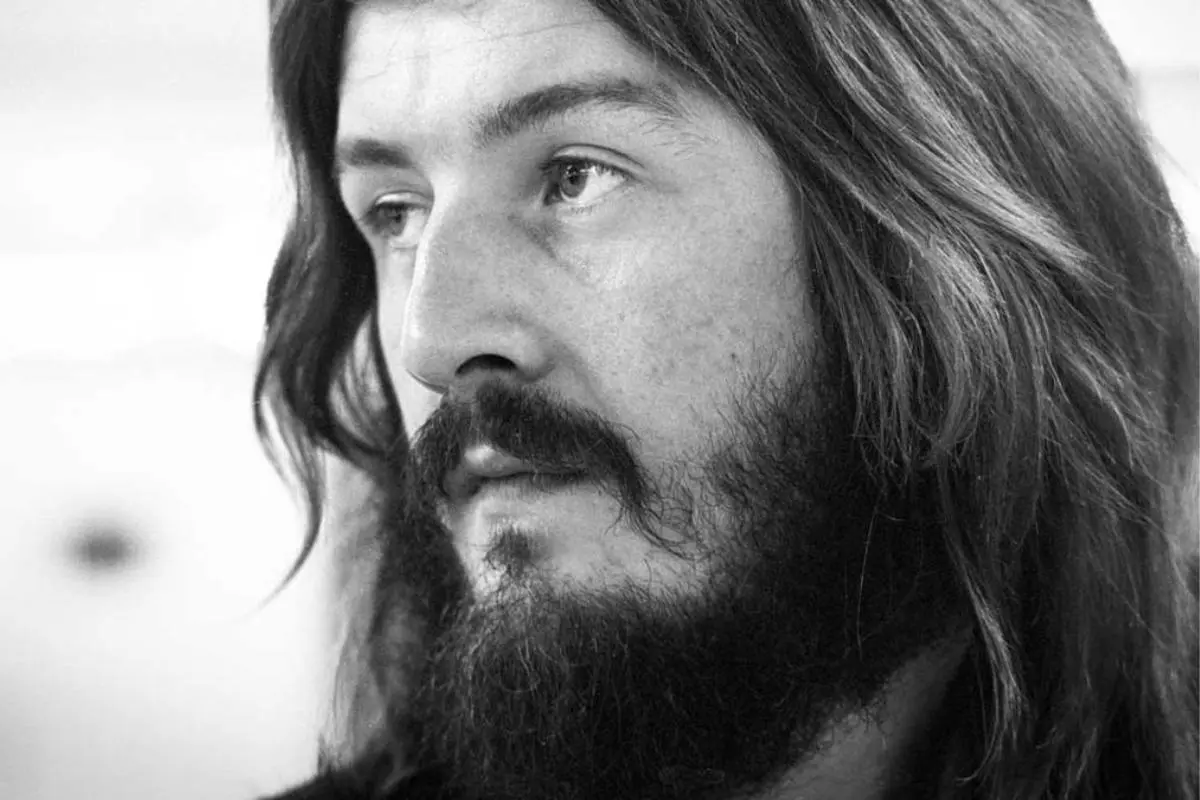

John Bonham, meanwhile, wasn’t merely loud or fast. He was heavy in the way a great boxer is heavy: weight behind every motion, a deep pocket, and a groove that could carry a stadium on its back. His legacy is so strong that even conservative lists of greatest drummers treat him as a top-tier benchmark.

Put those two in the same sentence and fans instinctively imagine sparks. Put them in the same room and the story basically writes itself.

Context matters: Led Zeppelin’s 1977 tour was a pressure cooker

Led Zeppelin’s 1977 North American Tour was colossal in scale and reputation, but it was also complicated: long shows, intense logistics, and a band balancing peak demand with very real turbulence. That mix is fertile soil for myths, because everyone assumes something outrageous must have happened somewhere.

Musically, Zeppelin were still operating like a top-of-the-food-chain live act. And while fans often connect the tour to the Presence era, it’s worth remembering that Presence arrived in 1976 and the band’s live sets mixed new material with established giants as reflected in documented 1977 setlists.

What we can say with confidence about the “meeting of legends”

Even if you strip away the unverified “Moon sat behind Bonham’s kit mid-show” detail, the underlying themes are real and important:

- Moon and Bonham were peers in a tiny circle of drummers who changed what rock drumming could be.

- The Who and Led Zeppelin were both defining live bands in the 1970s, with reputations built as much on volume and risk as on precision – an era still closely associated with Moon’s mythic, larger-than-life live reputation.

- Backstage cross-pollination was part of the era’s DNA. Not every jam made the history books, but plenty happened beyond microphones and setlist notes.

In other words: the “camaraderie” angle isn’t a Hallmark overlay. It is a realistic description of how rock ecosystems worked, especially among bands that lived on the road.

So where did the story come from?

Most persistent rock legends form the same way: a real relationship + a plausible scenario + a few enthusiastic retellings that grow teeth over time. In this case, the scenario is extremely plausible. Moon was known to show up where he wasn’t scheduled, and Zeppelin’s 1977 run had enough spectacle to make “anything is possible” feel like documentation.

But plausibility is not proof. If you want to treat the claim responsibly, treat it the way historians treat oral tradition: interesting, culturally revealing, but in need of corroboration.

A practical test: what would “proof” look like?

If Moon truly stepped in during a Zeppelin set in 1977, you would expect at least one of these to surface clearly:

- A contemporary review (newspaper or major magazine) describing the sit-in in plain terms.

- Audio/video with a traceable lineage, not just a random clip with a caption.

- Band/crew testimony on record, ideally in a book, documentary, or reputable interview.

- Setlist documentation that consistently notes the guest appearance across multiple archives.

Fan databases can be helpful for leads, but they can also propagate a single error at scale. Treat them as a starting point, not a judge’s ruling – especially when relying on high-level summaries of a band’s legacy rather than show-by-show documentation.

The drumming chemistry fans imagine (and why it’s so compelling)

Part of the reason people want this to be true is the musical “what if.” Moon and Bonham sat on opposite ends of the rock-drummer spectrum, and that contrast is the hook.

| Trait | Keith Moon | John Bonham |

|---|---|---|

| Core strength | Explosive fills, constant motion | Massive groove, deep pocket |

| Typical feel | Forward-leaning, frantic energy | Laid back but crushing |

| Band function | Co-lead instrument inside The Who’s chaos | Foundation under Zeppelin’s swing and weight |

If Moon really did sit in, even briefly, it would have been like dropping a firework into a steam engine. You can almost hear the crowd roar just imagining the first misplaced-but-glorious tom run.

The edgy angle: rock history sells chaos, not footnotes

Here’s the provocative claim: we romanticize “golden age” rock partly because it lets us forgive sloppiness as authenticity. Legends like this survive because they fit our preferred narrative: the 1970s as a lawless paradise where geniuses and lunatics shared drum risers on a whim.

That romance is fun, but it also erases the professional reality. Zeppelin’s 1977 operation was a high-stakes machine, and a surprise drummer swap in the middle of a stadium show would have been a massive risk to tempo, arrangements, cues, and liability. That doesn’t make it impossible, but it raises the bar for evidence.

What you can verify today (without killing the magic)

If you’re a fan who wants to dig in and still have a good time doing it, aim for verifiable anchors and build outward:

- Confirm the tour framework and likely dates where Moon could plausibly be in the same city as Zeppelin.

- Cross-check major setlist repositories for consistent notes about guests or unusual events.

- Use credible band biographies to confirm timelines, habits, and relationships, especially around Moon’s later years and Bonham’s working life.

- Compare multiple reference-quality profiles so you don’t inherit one writer’s embellished anecdote as “fact.”

Moon’s real legacy, Bonham’s real legacy: bigger than any one night

Keith Moon’s greatness isn’t dependent on a Zeppelin cameo. He remains a defining rock drummer because he treated the kit like a storytelling engine, constantly reacting to vocals and guitar, and turning simple structures into adrenaline events.

Bonham’s greatness isn’t dependent on “winning” a hypothetical drum duel either. His playing became a template for hard rock and beyond, and his name is still invoked as shorthand for taste, power, and feel.

And Led Zeppelin’s status at their peak is not in dispute: they were a dominant force in rock culture, album sales, and live reputation, even when the story around them got louder than the music.

Conclusion: treat the sit-in like a myth with a mission

The Keith Moon-Led Zeppelin 1977 sit-in story endures because it captures something true about the era: massive personalities, mutual admiration among musicians, and a scene that rewarded risk. The specific claim that Moon replaced Bonham onstage during the 1977 tour is not easily confirmed with high-grade documentation, so it deserves a careful label: legendary, plausible, but unproven in the clean way fans repeat it.

Believe it as a vibe if you want. Just don’t confuse vibe with evidence, because rock history is already loud enough without us turning every rumor into a monument.