Mike Bloomfield’s memory of being 17, hauling his guitar into “black places” where you either held your own or got exposed as a punk, cuts right to the core of what the blues meant to him.

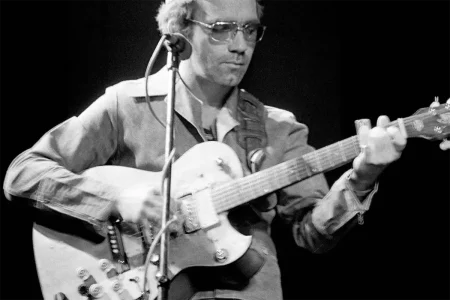

Born in Chicago in 1943, Bloomfield became one of the first rock-era stars judged almost entirely on his guitar work, from Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited” and the Paul Butterfield Blues Band to The Electric Flag, later earning spots on “greatest guitarist” lists and induction into both the Blues and Rock and Roll Halls of Fame.

“When I was 17, I thought I was good enough to gig in black places and hold my own… Several guys took me to be almost like I was their son – Big Joe Williams, Sunnyland Slim, and Otis Spann… What I learned from them was invaluable. A way of life, a way of thinking… By then it was a scholarly thing. Like Paul Oliver and Sam Charters, I wanted to know the story of the blues, and the best way for me to learn was to actually meet the guys.”

From rich kid to South Side outsider

Bloomfield did not come from the sharecropper shacks romanticised in too many blues clichés. He grew up in an affluent Jewish family on Chicago’s North Shore, destined for the family food-service business until the guitar and the radio hijacked his life, as detailed in a major Bloomfield biography.

According to friends and biographers, he was a misfit at prep schools, a troublemaker more interested in 45s than grades. Once he discovered Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf on stations like WVON, he followed the sound to the South Side, where his family’s maid literally walked him into clubs and introduced him to the men behind the records.

By his mid-teens Bloomfield was already jamming onstage with Muddy, Wolf, Little Walter and Otis Rush – a pudgy white kid in expensive clothes, standing in front of black audiences who had no reason to be generous if he faked a single note, as remembered in Chicago public radio’s account of his early years on the South Side.

“You had to hold your own” – the reality of black clubs

Bloomfield’s line about “black places” was not swagger; it was survival strategy. In those rooms, timing and tone mattered more than pedigree, and the quickest way to get booed was to show off without understanding the groove.

Holding your own meant a few brutal, practical things:

- Knowing the common blues keys and turnarounds without asking.

- Locking into the drummer’s shuffle and the bass player’s feel, not your own ego.

- Quoting the right licks from B.B., T-Bone, Elmore or Freddie in the right place – and then saying something of your own.

- Showing respect to the bandleader and elders, onstage and off.

Bloomfield was tolerated at first as a curiosity, but the veterans quickly realised he was serious. B.B. King, Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy all singled him out as a white kid who genuinely understood the music, not just the notes.

Adopted by the elders: Big Joe, Sunnyland and Spann

In the quote above Bloomfield names three men who “took me to be like their kid”: Big Joe Williams, Sunnyland Slim and Otis Spann. That list alone tells you how deep his apprenticeship ran.

| Mentor | Role in blues | What Bloomfield absorbed |

|---|---|---|

| Big Joe Williams | Delta singer-guitarist, king of the nine-string guitar | Rugged timing, percussive rhythm, the idea that sound can be wild, buzzing and almost “wrong” yet totally right |

| Sunnyland Slim | Mississippi-born pianist, key architect of postwar Chicago blues | How piano and guitar converse in a band, and how to drive a song with left-hand rhythm as much as solos |

| Otis Spann | Muddy Waters’ piano cornerstone and arguably the definitive Chicago blues pianist | Dynamic shading, call-and-response phrasing, and the emotional weight behind even simple progressions |

Big Joe in particular became a kind of surrogate father on the road. Decades later, a Vintage Guitar piece would note a 1963 recording of Williams at Chicago’s Fickle Pickle that Bloomfield himself helped book, with Bloomfield, Sunnyland and Washboard Sam listed as sidemen, proof of how closely their worlds had intertwined.

Bloomfield later wrote and recorded a devastatingly funny, affectionate road story called “Me and Big Joe” about their time hustling one-nighters together. It is not the voice of a tourist; it is the voice of a slightly terrified kid trying to live up to his mentor’s expectations in rooms where no one cared who your parents were, a tone that comes through vividly in radio recollections of that partnership.

From bar-band rat to field researcher

By the early 1960s Bloomfield had flipped the script: he was no longer just sneaking into South Side bars, he was actively bringing forgotten masters to new audiences. He ran Tuesday-night blues showcases at the Fickle Pickle and helped make Big John’s a North Side laboratory where black South Side bands suddenly found better-paying gigs in front of mixed crowds.

At the same time he was interviewing and taping players like Tampa Red, Kokomo Arnold, Jazz Gillum and Robert Nighthawk, quietly building an oral history archive while everyone else his age was worried about folk-club set lists, as noted in Chicago’s remembrance of his fieldwork.

Bloomfield name-checks British historian Paul Oliver and American writer Sam Charters in that quote for a reason. Oliver’s book “The Story of the Blues” and Charters’ earlier “The Country Blues” were the first serious attempts to map the music’s history and social context, and they lit a fire under a whole generation of blues nerds, Bloomfield included.

The difference is that Bloomfield was not just reading their work; he was walking into the same shotgun houses and West Side bars, guitar in hand, asking the musicians to show him how the songs actually felt under the fingers.

Rewiring the electric guitar vocabulary

When Bloomfield finally stepped into the broader rock world – first through the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, then backing Dylan at Newport, and later with Super Session – he brought that entire education with him. His move from Fender Telecaster and Duo-Sonic to a battered Gibson Les Paul that defined his thick, singing tone helped influence everyone from Carlos Santana to Jerry Garcia.

On this site we have looked at Duane Allman as a studio alchemist whose tone could “wail, weep and roar” at will; Allman’s session work and slide sound form a useful parallel to Bloomfield, who belongs in that same small club of players who changed what electric guitar could sound like simply by chasing the voices of their blues heroes harder than anyone else.

Lists of the greatest guitarists tend to foreground names like Hendrix, Page, B.B. King and Muddy Waters, but you cannot honestly tell the story of modern blues-rock guitar without the Jewish kid from Chicago who learned his craft under those men’s gaze, even if many “greatest guitarists” rundowns only mention him in passing.

“If You Love These Blues” – paying the debt back

By the mid-1970s Bloomfield was disgusted enough with the music business that he ducked most obvious career moves. Instead, he made the record that best explains the scholarly edge in his quote: “If You Love These Blues, Play ‘Em as You Please.”

Recorded in 1976 and conceived as a kind of guided tour through regional blues styles, the album combined Bloomfield’s playing with his spoken introductions, in which he explains who he is paying tribute to and what to listen for in each tune, a structure laid out in the Ace Records reissue notes.

He meant it as a way to repay the debt he felt to the black blues and white hillbilly performers who had schooled him, and it ended up being acclaimed as a concise audio history lesson as much as a guitar record, even garnering a Grammy nomination for Best Traditional Recording, according to later biographical accounts.

Chicago’s public radio later highlighted that Bloomfield himself called it “the best I’ve ever played on record” – a rare moment where this anti-star admitted he might have finally captured what he heard in his head when he was 17 on the South Side, as recalled in their tribute broadcast.

Apprenticeship or appropriation?

It is fashionable now to flatten every white blues story into a simple tale of cultural theft. There is truth in the criticism: Bloomfield’s fame and session work helped redirect money and attention away from many of the black elders he loved.

But it is also intellectually lazy to lump him in with tourists who learned three licks off a Muddy Waters LP and cashed in. Bloomfield spent years in dangerous neighborhoods, getting humiliated, corrected, punched in, and slowly accepted by musicians who had zero patience for inauthenticity – some of whom, like Big Joe, explicitly described him as family, a point underscored in profiles of Big Joe Williams’ later years.

He then used his platform to book, record and evangelise those same players in clubs and on records, in a way that paralleled what scholars like Oliver and Charters were doing from their tape machines and typewriters, a convergence you can trace by reading both Oliver’s history of the blues and Charters’ fieldwork classic.

What modern players can actually learn from Bloomfield

- Treat the tradition as a living classroom. Bloomfield did not learn the blues from tablature; he learned it by sitting a few feet away from Muddy and Big Joe, copying and then asking questions.

- Document as you go. He recorded interviews, organised gigs and later cut an instructional record that doubles as oral history. Your phone can do what his reel-to-reel did; use it.

- Get out of your comfort zone. He walked from the North Shore into neighborhoods his parents would have warned him about, because the music demanded it. There is no online substitute for intimidating rooms and unforgiving audiences.

- Fuse scholarship and feel. Bloomfield could cite Charters and Oliver, but he also bent strings like his life depended on it. Knowing dates and discographies is useless if your vibrato does not say anything.

Conclusion: The kid who did his homework onstage

Mike Bloomfield’s recollection of proving himself in “black places” is not just a colourful anecdote. It is the hinge connecting a privileged upbringing, a brutal musical apprenticeship, and a lifelong obsession with understanding where the blues came from and who paid the price for it, themes explored in detail in the oral history “If You Love These Blues: An Oral History”.

For listeners raised on the polished rock of the 1970s and 1980s, revisiting Bloomfield is a reminder that great guitar playing is not about pyrotechnics or gear lists, but about the courage to walk into someone else’s world, shut up, and learn. That is what he did at 17, and it is why his best work still hits harder than most modern “blues” records combined.