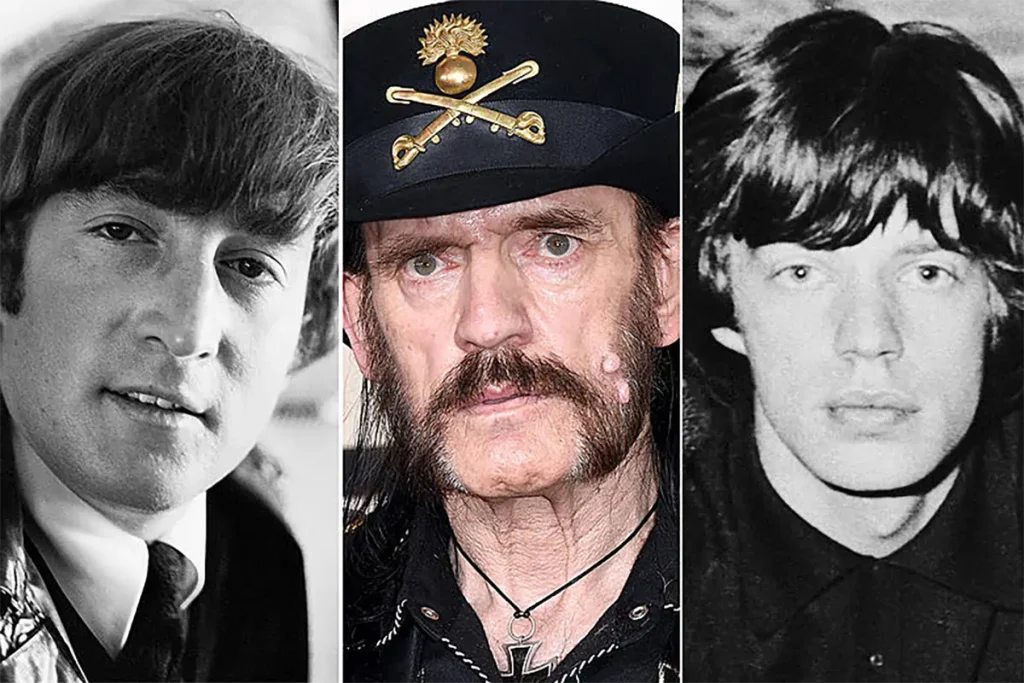

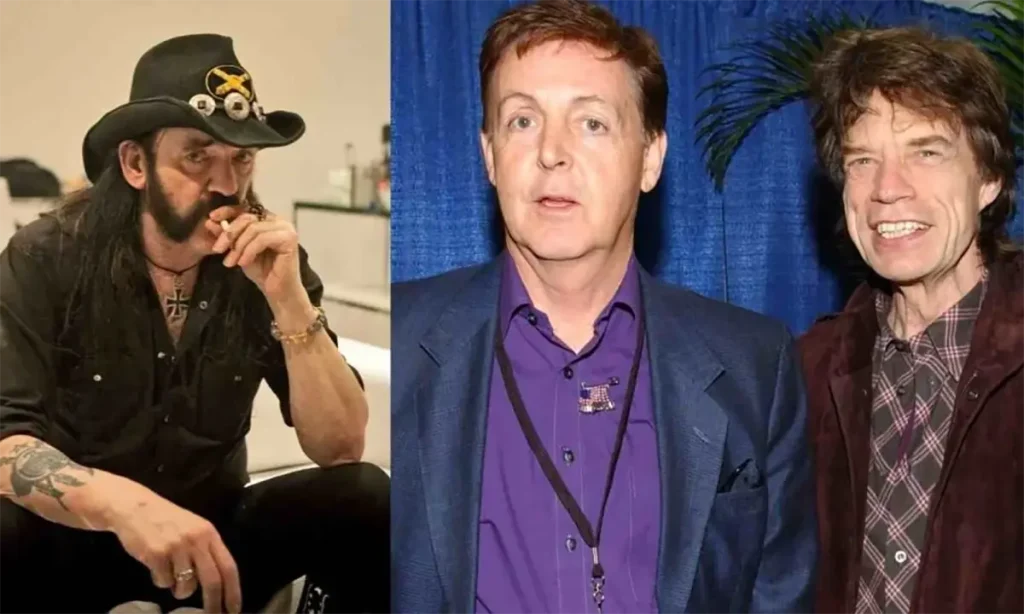

The Beatles were hard men too. Brian Epstein cleaned them up for mass consumption, but they were anything but sissies. They were from Liverpool, which is like Hamburg or Norfolk, Virginia a hard, sea-farin town, all these dockers and sailors around all the time who would beat the piss out of you if you so much as winked at them. Ringo is from the Dingle, which is like the f***ing Bronx. The Rolling Stones were the mummys boys they were all college students from the outskirts of London. They went to starve in London, but it was by choice, to give themselves some sort of aura of disrespectability. I did like the Stones, but they were never anywhere near the Beatles not for humour, not for originality, not for songs, not for presentation. All they had was Mick Jagger dancing about. Fair enough, the Stones made great records, but they were always s**t on stage, whereas the Beatles were the gear. – Lemmy Kilmister

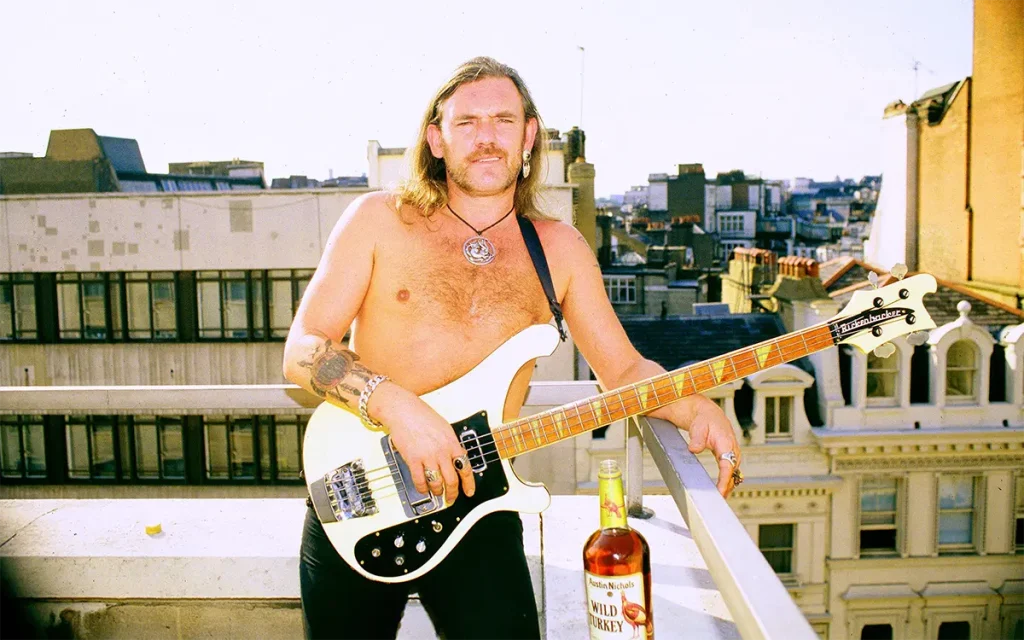

When a man like Lemmy Kilmister calls you a “hard man,” it is not a Hallmark compliment. It is a badge earned in sweat, blood and bad decisions. In his autobiography, the Motörhead frontman laid into the mythology of 60s rock and flipped one of its favorite binaries on its head: in his view, The Beatles were the real tough guys, and The Rolling Stones were the college-boy pretenders.

It is a wild quote, full of swearing and scorn, but it is also a sharp piece of rock criticism. Read closely, Lemmy is not only talking about fights outside Liverpool pubs. He is talking about authenticity, songwriting, stage power and the machinery that sells rebellion back to the masses.

Lemmy’s brutal verdict on Beatles vs Stones

In White Line Fever, Lemmy describes The Beatles as “hard men” from the docks of Liverpool, cleaned up by Brian Epstein “for mass consumption” but anything but sissies. He namechecks Ringo’s rough Dingle neighborhood and contrasts it with “mummy’s boys” in The Rolling Stones, whom he paints as college kids from the London outskirts who chose bohemian poverty for effect.

Then he really twists the knife. He says the Stones were “never anywhere near The Beatles” for humor, originality, songs or presentation. In Lemmy’s eyes they had Mick Jagger dancing about, some great records on tape, but they were “s**t on stage,” while The Beatles were “the gear” live.

This is not coming from a pop historian but from a man whose life changed when he heard The Beatles. Lemmy saw them at The Cavern, learned guitar by playing along with Please Please Me, and later fronted one of the loudest bands in history with that same mix of melody and menace he heard in the Liverpool lads.

Liverpool & Hamburg vs the art school Stones

How Liverpool and Hamburg hardened The Beatles

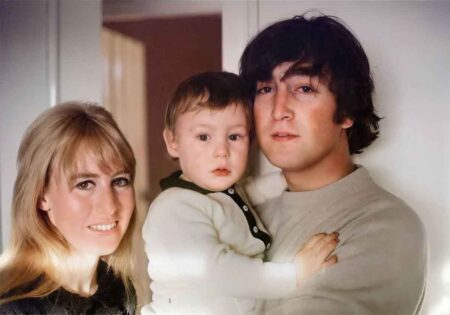

Liverpool in the 50s was not a boho playground. It was a bombed and battered port, full of dockers, sailors, drinking clubs and violence. Before Epstein’s suits, the young Beatles were leather-clad Teddy Boys idolising Gene Vincent, more juvenile delinquent than cuddly mop top. Brian Epstein’s decision to swap leather for matching suits turned that raw energy into something he could sell without erasing their toughness.

Hamburg turned that attitude into steel. On the Reeperbahn, surrounded by prostitutes, gangsters and drunk sailors, The Beatles played in clubs like the Indra, Kaiserkeller and Top Ten for seven or eight hours a night, seven nights a week. During one Top Ten residency they clocked 92 consecutive nights and more than 500 hours on stage, stretching songs into 15 minute workouts, improvising solos, doing anything to keep rough crowds interested.

Local bouncers included ex-boxers who had literally killed sailors in street fights, hired to keep order around the band. George Harrison later called Hamburg their apprenticeship, where they learned to put on a show rather than just stand and strum. Beatles Magazine’s account of their Cavern days is blunt about their look at this point: black leather, rockabilly hair, and a vibe that suggested they were more likely to shank you on the way out than sign an autograph.

And it was not just image. John Lennon later admitted that as a young man he “fought men and … hit women,” calling himself a violent person who only later learned to regret it and preach peace. His journey from self-confessed abuser to outspoken feminist campaigner shows just how far those instincts had to travel.

“Mummy’s boys”? The Stones’ student roots

Now put that next to the early Stones. Mick Jagger was born into a middle class Dartford family, sang in a church choir and studied at the London School of Economics before dropping out when the band took off. Keith Richards spent his late teens at Sidcup Art College, part of a now famous pipeline that produced a whole generation of rock musicians from British art schools.

These were not soft people by any stretch, but they were literate suburban kids, not waterfront scrappers. Lemmy’s “mummy’s boys” jibe is exaggerated, yet it nails a real cultural divide: dockside Liverpool vs grammar school Kent and art college London.

And crucially, the Stones’ bad reputation was, at least at first, a management strategy. Andrew Loog Oldham, who had worked in Beatles PR, saw that he could not sell another neat suit band. John Covach points out that Oldham deliberately rebranded them as the anti-Beatles, cultivating an image of danger, sex and disorder when their original look was closer to tidy R&B hopefuls. A CBS “Beatles vs. Stones” feature shows how Oldham first tried dressing them like The Beatles, then pivoted hard into “the band your parents loved to hate,” encouraging them to be as “nasty” and surly in public as possible.

So Lemmy is really saying this: the band sold as safe turned out to be full of genuine hard cases, and the band sold as degenerates were, on paper, art school and business school kids with a very clever publicist.

On stage: were the Stones really “s**t” and The Beatles “gear”?

The Beatles: brutal working band with jokes

Hamburg and the Cavern made The Beatles one of the most seasoned live outfits on earth before they ever cut a major-label LP. Playing seven or eight hours a night, they learned to change arrangements on the fly, extend vamps, swap solos and keep their energy terrifyingly high. Lennon remembered songs blowing out to 20 minutes with endless solos simply because they had time to kill.

That grind forged a band that could lock in like a soul rhythm section and still crack jokes between verses. Watch early Cavern or BBC clips and you see a savage rhythm guitarist in Lennon, a relentlessly melodic yet muscular bassist in McCartney, and a drummer in Ringo whose feel is closer to New Orleans shuffle than polite British pop. They were loud, rough and hilarious, not the fragile studio monks later mythologised.

The tragedy is that Beatlemania destroyed their live reputation. As Covach notes, primitive sound systems meant that by the mid 60s the crowd was louder than the band, and their inability to hear themselves was a core reason they quit touring in 1966. The public mostly remembers the chaotic stadium years, not the pre-fame band that could blow almost anyone off a club stage.

The Stones: uneven early, dominant later

Early Stones shows were ragged. They were still wrestling with borrowed blues material, Jagger’s frontman persona and half-baked PA systems. Oldham pushed them to move more, sneer more and let Jagger’s sexuality carry shows that were not always musically tight. If Lemmy mainly saw that era, his contempt for their stagecraft makes sense.

But the story does not end there. By the 1969 American tour the Stones had become, in effect, the template for modern arena rock. Researchers at the University of Rochester argue that those late 60s tours, with huge sound systems and carefully worked setlists, marked the shift from pop concerts to the stadium rock era. Our look at Altamont shows the other, darker side of that transition: a band powerful enough live to draw hundreds of thousands into a desert speedway, yet naive enough to let the Hells Angels run security, with fatal results.

And if you want proof that the Stones could rise to the moment on stage, read about the 1981 Halloween show in a Texas rainstorm: the band pushing through a downpour to ignite 70,000 soaked fans, the music turning defiance into a kind of ritual. Whatever you think of Jagger’s prancing, this is not the curriculum vitae of a permanently “s**t” live act.

| Era | The Beatles | The Rolling Stones |

|---|---|---|

| 1960-62 | Leather-clad, Hamburg-hardened club killers, hours of stage time every night. | Young R&B covers band, still finding its feet, image not yet fixed. |

| 1963-66 | Best club band in Britain, then drowned out by stadium hysteria, quit touring in frustration. | Rapid growth into aggressive live unit, Oldham turning them into anti-Beatles pinups. |

| 1969 onward | Off the road, innovating in the studio. | Masters of big-room rock, from Altamont’s chaos to meticulously staged mega tours. |

Lemmy’s verdict on live shows is less history and more taste. He wanted speed, volume, black humor and songs that punched harder than the PA. Early Beatles gave him that in sweaty clubs. Early Stones, to his ears, did not.

Songs, studio magic and humour: was Lemmy right?

Originality and studio courage

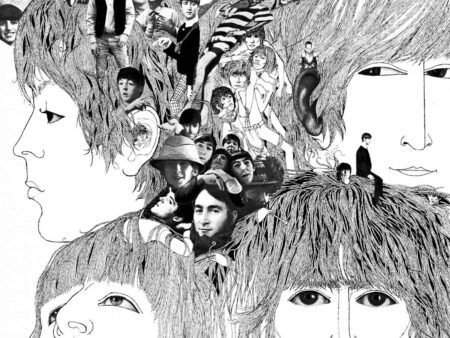

On originality, Lemmy is on very solid ground. The Beatles’ mid 60s run simply has no equivalent. On Revolver, they fused Indian drones, tape loops, backward guitar solos and avant garde tape splicing into concise pop songs. They stacked string octets under “Eleanor Rigby” and turned “Tomorrow Never Knows” into a psychedelic mantra built from spinning tape machines, all under insane commercial pressure.

Our Revolver piece makes the point clearly: by 1966 they were not just a band but “sonic architects,” rewriting the rules of how records could sound. Later generations of rock, metal and experimental music – Lemmy’s included – fed directly off that freedom.

The Stones were original in a different way. Their early mission was to champion and then mutate American blues. Take a look at their blues revival shows, they dug deep into Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and Slim Harpo, then cranked those grooves through British amps until riffs like “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” and “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” became new folk music for the electric age. Keith Richards’ open G riffs are as instantly recognisable as any McCartney bassline.

So yes, The Beatles were more sonically adventurous and stylistically wide ranging. The Stones, though, built a different kind of originality: a dark, riff-based language of swagger and menace that still underpins rock guitar today.

Humour and presentation

On humour and presentation, Lemmy has a point and it bites. The Beatles walked into press conferences and variety shows with razor sharp wit, turning the whole circus into their own comedy sketch.

The Stones were funny in a drier, more contemptuous way, but Oldham’s branding demanded that they look sullen, louche and vaguely criminal. That made for fantastic posters and nervous parents, yet it also boxed them into a narrower emotional palette. Beatles gigs felt like raucous parties thrown by four clever mates. Stones gigs felt like a ritual of sex and doom with Jagger as high priest.

What musicians can steal from this feud

Beyond the tribalism, Lemmy’s rant hides some hard won lessons for anyone who plays an instrument.

- Grind beats glamour. Hundreds of Hamburg and Cavern hours turned average kids into a terrifyingly tight unit. There is no shortcut for that kind of repetition.

- Songs outlast image. Lemmy ultimately judges both bands on writing. He praises Beatles melodies and structures far more than their haircuts. If your tunes are bland, no amount of eyeliner or leather will save you.

- Control your image, but do not believe it. The Stones cashed in on being the anti-Beatles, and it worked, but research into their marketing shows that posture was as calculated as Epstein’s suits. Remember that the “dangerous” band in leather might be full of bookish kids, and the clean cut boys might be starting bar fights.

- Toughness is what you survive, not where you studied. Lennon went from violent Teddy Boy to regretful peace obsessive. Jagger went from LSE student to fronting some of the most debauched tours in rock history. Real hardness is the ability to evolve without losing your edge.

- Study both sides. Put on early live Beatles, then the Stones’ late 60s bootlegs. Listen to the bass lines, drum feel, and how the frontman controls the room. Steal what works for your own band.

Beatles vs Stones: Lemmy’s verdict, your call

Lemmy’s quote is incendiary because it attacks a comfortable myth. The record industry sold The Beatles as nice boys and The Rolling Stones as the thugs. The truth is messier and, frankly, more interesting. The Beatles were sharper, stranger and tougher than the brand allowed. The Stones were smarter, more calculated and more educated than the “street fighting” logo suggested.

Was Lemmy right that the Beatles “were the gear” and the Stones were never their equal? On songs, range and studio daring, you could argue he was. On live power after 1968, history gives the Stones a very strong case. In the end, the best way to honour Lemmy’s provocation is not to vote in some imaginary poll but to turn the volume up: crank Revolver, crank Exile on Main St., and listen for the hard men in both.