John Bonham did not just play the drums in Led Zeppelin, he detonated them. Yet behind the legend of smashed hotel bars and deafened audiences was a self taught player who thought more like a jazz arranger than a meat and potatoes rock basher.

From Redditch kid to hammer of the gods

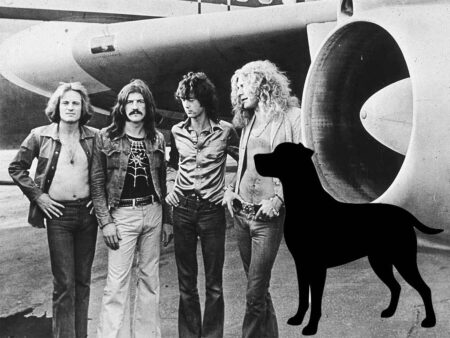

John Henry Bonham was born in 1948 in Redditch, Worcestershire, and by five he was cobbling together drum kits from coffee tins while copying the swing of Max Roach and Gene Krupa. Mostly self taught, he moved through Midlands bands while working as an apprentice carpenter, then joined singer Robert Plant in Band of Joy before guitarist Jimmy Page poached him for the New Yardbirds, soon renamed Led Zeppelin. Offstage he was a family man with wife Pat and children Jason and Zoë, but also a car and motorbike obsessive whose drinking became notorious. In September 1980, after consuming a huge quantity of vodka during rehearsals for a US tour, he choked in his sleep at Page’s house and died at 32, and the remaining members ended Led Zeppelin rather than replace him.

Inside Bonham’s drumming brain

Jazz hands in a heavy rock band

Bonham’s secret was that he approached heavy rock with a jazz drummer’s imagination. He soaked up big band players like Buddy Rich, Max Roach and Gene Krupa, along with funk and soul innovators such as Clyde Stubblefield and Bernard Purdie, then folded their swing and syncopation into Zeppelin riffs. You can hear it in the Little Richard inspired intro to “Rock And Roll” and the funk slink under “Black Dog,” where he treats the beat more like a horn chart than a metronome.

Far from the cartoon image of a caveman at the kit, peers describe him as a studious drum nerd who knew the lineage of every lick he played. He borrowed bare hand techniques from Papa Jo Jones and Joe Morello, incorporated waltz like phrasing straight out of Max Roach, and then pushed those ideas through sheer volume. The result was a drummer who could swing, shuffle or bludgeon without ever losing the pulse.

Triplets, shuffles and that monstrous right foot

Listen closely and Bonham’s language is built on triplets and sixtuplets, not straight eighths. Detailed transcriptions show how he turns lines of six notes into sculpted phrases, often accenting the last note of each triplet on the kick drum to make fills sound like rolling thunder rather than busy chatter. Those same studies reveal his fondness for shifting between triplet and non triplet feels inside a single phrase, which is why a fill in “Kashmir” or a live “Since I’ve Been Loving You” can feel like the ground tilting under you.

Modern writers point out that Bonham was effectively playing “gospel chops” decades before that label existed. He loved hand foot triplets, frequently leading with his left hand so the figure moved across snare, rack tom and floor tom, creating a heavier, deeper sweep than the usual right led pattern. Combined with his single footed bass drum triplets in “Good Times Bad Times” and the half time shuffle in “Fool In The Rain,” he built grooves that sounded impossible yet sat perfectly in the song.

That balance of brutality and nuance is why contemporary educators still use him as a benchmark. Analyses of his playing highlight how he could move from whisper quiet ride cymbal textures to explosive crashes within a bar, all while keeping the backbeat immovable and the bass drum speaking in full sentences rather than single syllables. In tracks like “What Is and What Should Never Be” or “The Lemon Song,” he turns dynamics into drama rather than mere volume changes. Drumming profiles still hold him up as a model of musical power.

It is no accident that modern drumming roundups regularly place Bonham among the most influential players in history. Writers point to his mastery of huge drums, single pedal kick virtuosity and song first parts, and note that the intro to “When The Levee Breaks” remains one of the most sampled beats ever recorded. For rock and metal drummers, he is less a historical figure and more an unavoidable starting point.

The sound: huge drums, high tuning, ringing for days

The Ludwig artillery

If you want to understand how he drummed, you have to look at what he hit. Bonham’s classic Led Zeppelin era setup was a Ludwig kit anchored by a 26 x 14 inch bass drum, a 15 x 12 inch rack tom on a snare stand, and 16 x 16 plus 18 x 16 floor toms, a layout borrowed from his idol Buddy Rich. Over the years he cycled through natural maple, green sparkle, amber Vistalite acrylic, silver sparkle and finally stainless steel versions of that format, but the basic formula of one huge kick and two big floors never changed.

Drum techs and writers agree that the really radical move was how high he tuned those big shells. Bonham cranked his resonant heads tighter than the batters on toms and kick alike, so that a casual tap could produce a timpani like note, and he often left the front bass drum head unported to let the air column speak. This went against the dead, muffled 70s rock norm and gave him a tone that was both booming and pitched, a reason every hit on “When The Levee Breaks” or “Kashmir” sounds like someone slamming a door in a cathedral.

The Paiste roar

On top of those cannons he stacked bright, muscular cymbals that could keep up. By the early 70s he was a Paiste artist, famously pairing 15 inch 2002 Sound Edge hi hats with Giant Beat and later 2002 crashes and a massive 24 inch ride that doubled as an explosive crash. Official setups list combinations like 18 and 20 inch Giant Beats, 18 inch 2002 crashes and 24 inch 2002 rides, all chosen for volume and a wide, musical wash rather than subtle jazz shimmer.

This is why his cymbals tend to sound like another set of drums rather than background color. He often rode on the crash and saved lighter cymbal work for when the band dropped down, using them to frame guitar riffs instead of just marking time. In effect, he treated the whole kit as one tuned, ringing instrument rather than separate pieces to be muted and controlled.

How the studio turned Bonham into an earthquake

Engineers were smart enough to get out of his way. Early on, producer Glyn Johns discovered that placing a few microphones a little further from the kit created a massive, natural stereo picture of Bonham rather than a close miked thud. Accounts of those sessions describe Johns experimenting with two or three mics placed equidistant from the snare and higher in the room so the sound could breathe, which made every nuance of Bonham’s touch and tuning leap out of the speakers.

The definitive example is “When The Levee Breaks,” cut at the country manor Headley Grange. There, engineer Andy Johns set Bonham’s Ludwig kit in a tall stone lobby and hung a pair of Beyerdynamic M160 microphones up the stairwell, feeding them into aggressive Helios compressors and a Binson Echorec delay to create that famous “breathing” drum sound. With no close mics at all, the room itself became part of the groove, and the resulting break was so powerful that hip hop producers later chopped the opening bars for tracks like the Beastie Boys’ “Rhymin & Stealin.”

Bonham vs the rest of the drum world

One provocative modern take is that Bonham was not operating in a vacuum at all, he was standing on the shoulders of another hard hitting innovator. In interviews, Carmine Appice has described how Bonham studied his work with Vanilla Fudge, particularly the ending of their version of “Shotgun,” and folded that kind of theatrical, tom heavy slam into Zeppelin tracks like “Rock And Roll.” Appice is clear that he holds no grudge, but his comments underline that even the most worshipped rock drummer was borrowing and exaggerating ideas, not conjuring them from thin air.

Critics sometimes accuse Bonham of being all bombast, yet drummers who actually dissect his parts usually come away talking about touch and placement. Detailed breakdowns point to his use of ghost notes on snare to make slow grooves like “No Quarter” or “Ten Years Gone” breathe, and his surprising restraint in songs where a lesser player would have filled every gap. He knew when to leave space so that one monstrous fill or flam would feel like a punch to the chest rather than wallpaper, a point that many modern analyses emphasise.

Four essential Bonham performances to study

| Track | Album | What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

| Good Times Bad Times | Led Zeppelin | Single footed bass drum triplets that sound like a double pedal, and how the kick pattern becomes the hook of the song. |

| When The Levee Breaks | Led Zeppelin IV | The cavernous room sound, laid back pocket and how simple kick snare figures can feel massive with the right dynamics. |

| Fool In The Rain | In Through the Out Door | A half time shuffle with swung hi hats and ghosted snares, Bonham’s twist on the Bernard Purdie style groove. |

| Moby Dick | Led Zeppelin II | How he builds a long solo using motifs, hand drumming and dynamics instead of pure speed for its own sake. |

Stealing Bonzo’s tricks without losing your hearing

If you play, copying Bonham note for note misses the point. Start by tuning your drums higher than feels comfortable, especially the resonant heads, and resist the temptation to stuff the bass drum with pillows. Work on clean, loud single pedal strokes so you can play triplets and sixtuplets with one foot instead of hiding behind a double pedal.

Equally important is thinking like an arranger. Build simple, song serving grooves where the kick pattern and dynamics tell a story, then save the heavy artillery for the one fill that matters instead of every bar. Most of all, chase his feel, not just his licks: the way he leans on the backbeat, lets cymbals swell and leaves just enough space is what turned a loud British rock band into something that still feels dangerous every time the drums come in.