Elvis has been blamed for corrupting youth, saving rock, and reinventing Las Vegas. Now he has helped cost a Missouri judge his robe.

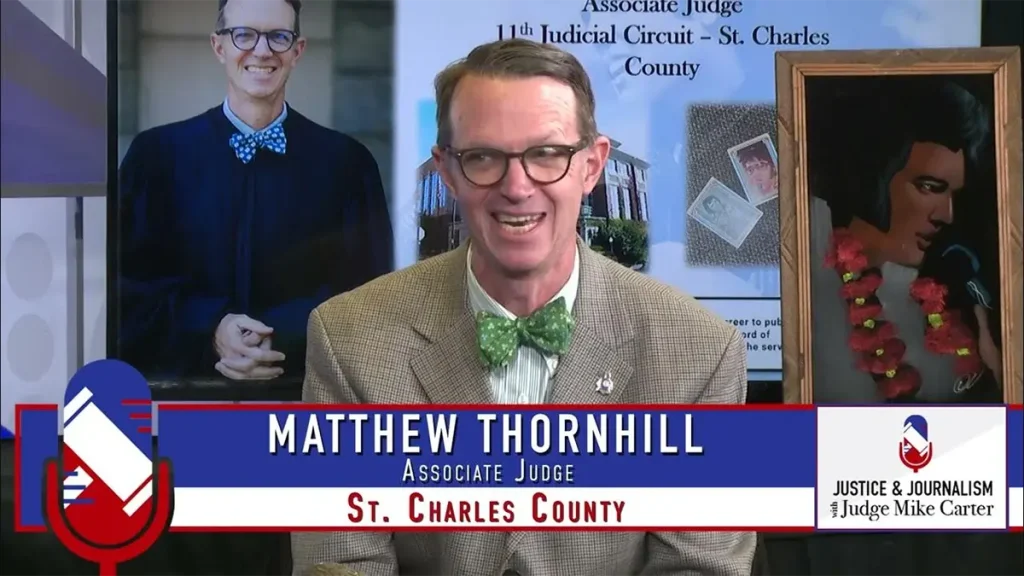

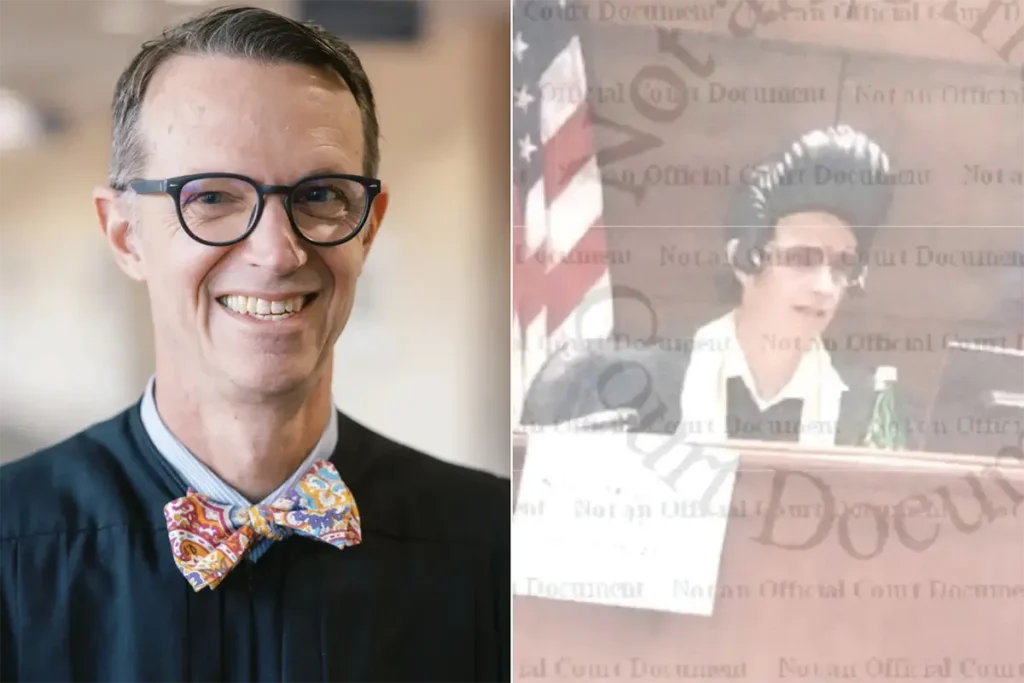

St. Charles County Circuit Judge Matthew Thornhill, a self-confessed superfan of the King, turned his courtroom into a kind of low-rent Elvis revue. The wig, the music and the jokes made for viral headlines, but the fallout is deadly serious: a formal ethics case, a forced exit from the bench, and a lifetime ban on serving as a judge in Missouri.

For music lovers, especially those who grew up with Elvis on the radio, this story is more than a punchline. It is a reminder that there are places where the soundtrack has to stop.

What exactly did the Elvis-loving judge do?

According to findings by Missouri’s Commission on Retirement, Removal and Discipline of Judges, Thornhill engaged in a string of Elvis-themed antics while presiding over real cases.

- Elvis wig on the bench: On Halloween, he appeared in court in an Elvis-style wig, and commission documents say there were several occasions when he wore an Elvis Presley wig in court while handling official business.

- Elvis music during oaths: Thornhill sometimes let litigants and witnesses choose how they wanted to be sworn in. One option involved him playing Elvis tracks from his phone while they took the oath.

- Irrelevant Elvis references: He reportedly worked in stray facts about Elvis, such as the singer’s birth or death dates, during proceedings where those details had nothing to do with the legal issues before him.

- Soundtrack to court business: The commission also alleged that he played Elvis songs as he entered the courtroom and at other moments during hearings, turning serious matters into something closer to a themed variety show.

None of this would be out of place at a Vegas tribute night. In a room where people can lose their liberty, their money or even their kids, it reads very differently. The commission concluded that his conduct undermined public confidence in the integrity of the judiciary and failed to maintain proper order and decorum.

The bigger problem: politics and personal favors from the bench

If this were only about a Halloween costume and some ill-timed Elvis tracks, the punishment might have been a public scolding. But the case against Thornhill went much further.

The same disciplinary filings describe two other categories of misconduct that have nothing to do with music and everything to do with power.

- Campaign talk in the courtroom: Thornhill, a Republican, was accused of mentioning his party affiliation and preferred candidates in front of litigants, witnesses and lawyers. In some instances he allegedly asked people if they had seen campaign signs attacking him as a judge, effectively dragging his own electoral politics into official proceedings.

- A “personal reference” in a family case: The commission says he hand-delivered a reference letter in a case involving termination of parental rights and adoption, vouching for a party in the case. Judges are generally barred from volunteering as character witnesses unless they are formally subpoenaed, because it blurs the line between neutral decision maker and advocate.

Mix in the Elvis material, and the picture is of a judge who treated the courtroom as his personal stage: part fan club meeting, part political coffee hour, part favor factory. That is why the punishment went far beyond “no more costumes.”

The punishment: suspension now, Elvis has to leave later

Rather than fight the charges, Thornhill signed a deal with the commission and effectively pleaded guilty in a written admission. In a November letter he acknowledged that the allegations were “substantially accurate” and that the commission could prove them at a hearing.

The agreement, as described in local coverage based on court documents, works like this:

- Six months of unpaid suspension from the bench.

- An 18 month return to judicial duties after that suspension.

- A mandatory, nonrevocable resignation at the end of that period.

- A permanent bar on holding any future judicial office in Missouri.

St. Louis Magazine notes that the timeline conveniently lines up with Missouri’s rule that judges aged 62 or older with twenty years of service can retire on full benefits. The negotiated exit lets Thornhill reach that milestone, then walk away, robe folded, pension intact.

In other words, the King impersonator gets banished from the bench, but not from the retirement system.

How Elvis became the costume of choice

Anyone who grew up with rock and roll knows why an aging Midwestern judge might reach for Elvis when he decides to “add levity” to his workday. Elvis is not just a singer; he is a visual shorthand for an entire era.

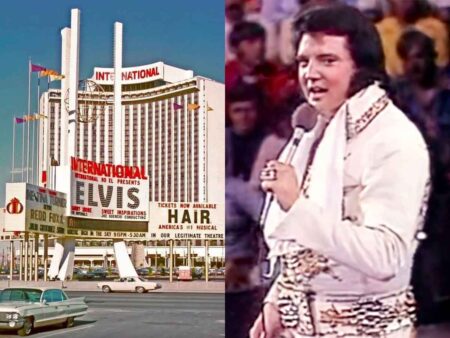

As we have written before, Elvis’s Las Vegas residency in the late 1960s and 70s cemented the look that tribute acts still copy: pumped-up pompadour, jeweled jumpsuits, capes and massive belts, all wrapped around a stage persona that was equal parts preacher, crooner and comic. That gaudy Vegas period created the template for the endless parade of Elvis wigs at Halloween parties, weddings and tacky chapels.

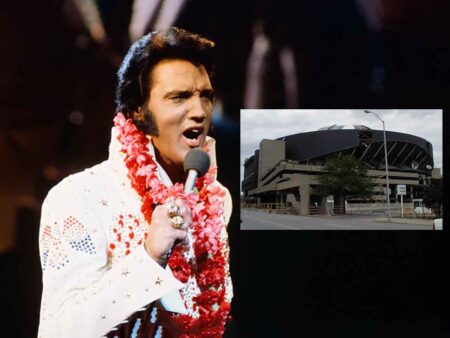

His last concert in Indianapolis was picked apart for decades afterward, with fans scrutinizing his voice, his body language, even his farewell lines for signs of what was to come. That obsessive focus helps explain why ordinary people and public figures alike keep slipping into Elvis drag. It is a way of borrowing that myth, if only for a night.

Thornhill told the commission that his wigs and music were meant to “add levity” and relax nervous litigants, not to mock the process. In a barroom, that might be charming. In a court of law, it plays as something closer to narcissism.

The rules judges have to play by

Missouri’s Commission on Retirement, Removal and Discipline of Judges exists for situations exactly like this. It is a constitutional body made up of judges, lawyers and lay members that investigates complaints about judicial misconduct and can recommend discipline, suspension or removal to the state supreme court.

Under Missouri Supreme Court Rule 12, the commission conducts investigations, holds formal proceedings when warranted and then files detailed findings of fact, legal conclusions and recommendations. The Supreme Court of Missouri reviews that record and enters whatever order it deems appropriate.

Behind the legal jargon are some fairly blunt expectations:

- Judges must promote confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.

- They must maintain order and decorum in their courtrooms.

- They have to avoid both actual impropriety and the appearance of impropriety.

- They are sharply limited in their political activity, particularly when they are on the bench or dealing with litigants who appear before them.

- They cannot casually use the prestige of their office to advance private interests, including stepping in as voluntary character witnesses.

According to the disciplinary filings, Thornhill’s Elvis routine was not treated as a harmless joke because it collided head on with several of those duties. Playing personal favorite music while administering oaths and dropping fanboy references in the middle of serious hearings does not read as neutral or solemn.

The political talk and the reference letter make things worse. At that point you are no longer the quirky judge with the wig. You are the officeholder blurring the line between campaign and courtroom, public trust and personal loyalty.

A judge with a history of boundary problems

If you dig into public records, this is not the first time Thornhill’s professional judgment has come under scrutiny. The Missouri Supreme Court’s discipline docket shows that he received a formal reprimand as a lawyer in 2008, years before becoming a judge. The listing does not spell out the underlying conduct on that page, but it does confirm that regulators had reason to question his ethics long before the wig showed up.

Seen in that light, the Elvis affair looks less like a one-off midlife crisis and more like the latest chapter in a career where the line between showmanship and professionalism kept getting tested.

Can music ever belong in a courtroom?

For readers who came of age when rock and roll itself was treated as dangerous, there is a certain irony here. Elvis was once the sound that respectable America wanted to ban from polite company. Now the establishment’s complaint is that he is too playful for the bench.

The truth is that music already appears in some corners of the justice system. A few specialty courts use songs and writing as part of addiction treatment or youth rehabilitation. In those settings, the music is part of a structured program designed to help defendants, agreed to by all involved.

What happened in Thornhill’s courtroom is different. He was not inviting people to share music that mattered to them. He was forcing them into his fandom while they stood under oath. There is a big difference between a probation officer suggesting you journal about a song that helped you through a tough time and a judge blasting his favorite artist while deciding whether you lose custody of your child.

Elvis himself built a career on walking the line between the sacred and the profane, mixing gospel roots with sensual swagger. That tension made for unforgettable records. It is the last thing you want injected into a custody hearing or a sentencing.

Elvis, power and knowing when to turn the music off

The headline about a “Missouri judge losing his job for wearing an Elvis wig” is irresistibly funny. The underlying story is not. At its core, this case is about what happens when someone entrusted with enormous power forgets that the day in court belongs to the public, not to his personal playlist.

Elvis will always have a place in American life. Our own deep dives into his Vegas years and final concerts show how enduring that fascination is, decades after his last bow. He still rules the wedding chapels, the karaoke bars, the tribute cruises and the costume racks every October.

But there are rooms where even the King has to stay outside. A criminal trial. A custody hearing. A courtroom where a frightened defendant is trying to understand whether their life is about to be torn apart. In those moments, justice needs less show and more silence.

Thornhill seems to understand that now. The rest of us can enjoy the music at home, in the car, or at the next nostalgia tour, and leave the wigs in the closet when it is time to sit in judgment.