It is easy to file Cream next to your classic rock records and forget about them. Their drummer, Ginger Baker, spent decades insisting that would be a mistake. In his mind he was never a rock player at all, and Cream were something far stranger.

Take him at his word for a moment. Imagine Cream not as a psychedelic blues band but as two hard bitten jazz musicians locking horns with a blues guitar hero in front of deafening stacks of amps. Suddenly his famous outburst about the group starts to sound less like cranky revisionism and more like a key to understanding a whole era.

I have never played rock: what Baker really meant

In a 2013 conversation with writer Marc Myers, Baker exploded at being called a rock drummer, snapping that Cream were two jazz players and a blues guitarist playing improvised music, never repeating themselves from night to night, and that his wild drum work came from jazz, not drugs. That rant echoed other moments when he flatly rejected the rock label and stressed the improvised nature of Cream’s music, and it was not just ego or annoyance at lazy labels. It was Baker trying to drag the discussion away from marketing categories and back to process.

For him, what mattered was not whether a tune sat next to Muddy Waters or Miles Davis in the record rack. What mattered was whether the band was listening, reacting and inventing in real time. On that score, he believed Cream behaved like a jazz group that just happened to be loud enough to peel paint.

Two jazz players and a blues guitarist: what that really means

Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker – a jazz engine in a rock band

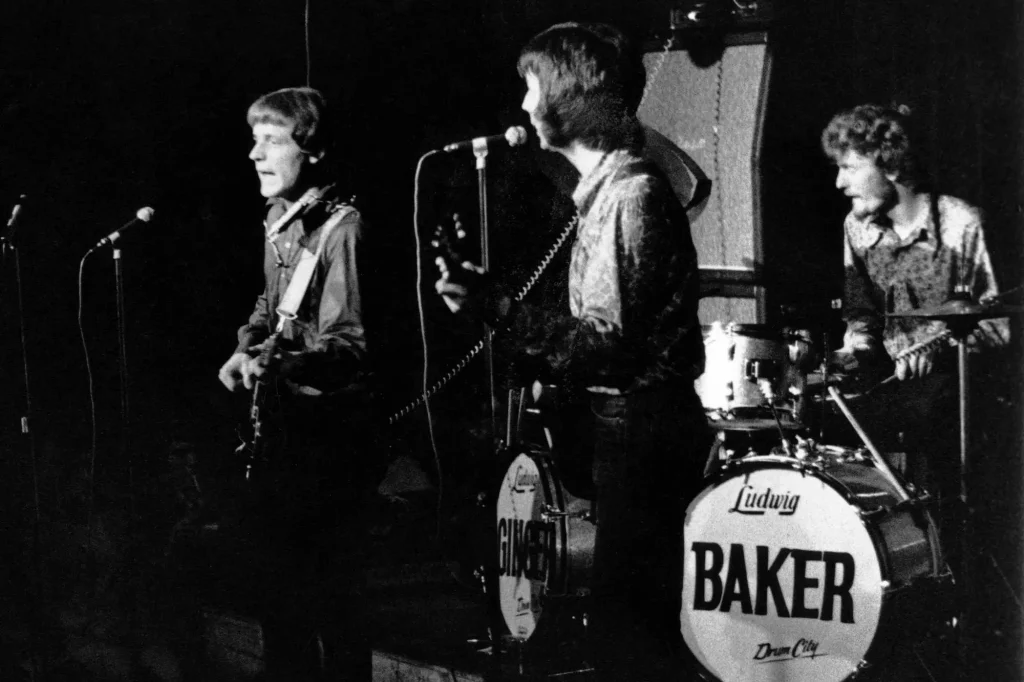

Baker cut his teeth in the 1950s British jazz scene, moving from trad groups into modern jazz and making his name in London clubs before joining Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated and then the Graham Bond Organization with bassist Jack Bruce. Those bands already fused bebop vocabulary with R&B grit, and both men learned to treat rhythm section roles as flexible and conversational rather than obedient.

By the time Cream formed, Baker and Bruce were thinking like a ferocious small jazz unit trapped inside a pop format. Bruce’s bass lines wandered melodically like a horn, Baker phrased across bar lines instead of sitting politely on the beat, and both men were ready to stretch any three chord tune until it resembled a late night club workout.

Eric Clapton – the blues purist outnumbered two to one

Eric Clapton walked into this with a very different toolkit. He was the blues prodigy of London, steeped in Freddie King and Robert Johnson, and fresh from the Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. His obsession was touch, tone and the emotional arc of blues phrasing, not polyrhythmic warfare.

As Cream became louder and more indulgent on stage, Clapton grew disillusioned. Hearing the Band’s album Music from Big Pink, with its restrained ensemble playing and song first mentality, he later felt he was in the wrong place with the wrong people doing the wrong thing, a shock that helped nudge him away from Cream’s volume arms race and toward more song based projects. In other words, the lone blues guitarist eventually fled the two jazz players.

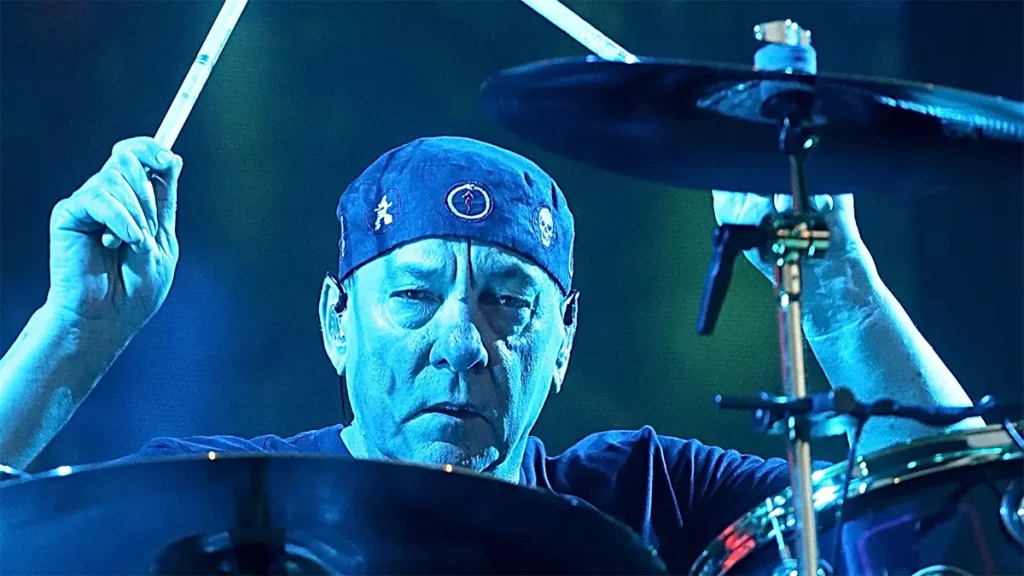

How jazz shaped Baker’s drumming in Cream

On his own site, Baker recalled being floored as a teenager by the famous Massey Hall quintet recording, studying Baby Dodds 78s and then being ushered into African drum records by his mentor Phil Seamen, experiences that convinced him rhythm could be conversational, elastic and far deeper than the simple backbeats dominating early pop and rock. In his rundown of early influences he makes it clear he was not copying rock drummers at all, he was translating what he heard from Max Roach, New Orleans pioneers and West African ensembles into a much louder context.

Those roots stayed obvious well into his later career. Reviewers of his jazz album Why? pointed to his reliance on tom toms instead of snare, African inflected patterns and muscular single stroke figures that sit somewhere between big band power and free jazz turbulence rather than tidy rock grooves. A contemporary review of Why? underlines how closely his late style still tracked his jazz and African inspirations. Listen back to Cream with that in mind and the supposedly heavy rock drumming starts to sound like a bebop drummer who has stumbled into a Marshall factory.

| Feature | Typical 60s rock drummer | Ginger Baker in Cream |

|---|---|---|

| Time feel | Rigid backbeat on 2 and 4 | Shifting ride patterns, pushes and pulls around the beat |

| Role in band | Support singer and guitar, stay out of the way | Co soloist, trading ideas with bass and guitar constantly |

| Rhythmic language | Straight eighths, simple fills, little syncopation | Triplets, polyrhythms, displaced accents, extended motifs |

| Use of drums | Snare and bass drum dominate, toms mostly for fills | Toms treated like tuned voices, central to the groove |

| Improvisation | Short, scripted solo spots if any | Long narrative solos, evolving textures, open ended forms |

Improvised mayhem: Cream on stage

Cream in the studio gave you three or four minute songs with hooks. Cream on stage gave you something closer to a freewheeling jazz trio that happened to know Sunshine of Your Love. Critics later noted that Baker effectively redefined rock drumming by dragging long, jazz style solos and complex rhythmic structures to the front of a power trio, and you can hear it in the sprawling live cuts that turned simple riffs into twenty minute journeys.

Those performances were not polite variations on themes, they were knife fights. Bruce might push a bass phrase across the bar line, Baker would answer with a flurry on the toms, Clapton would either ride the wave or get swallowed by it. Sometimes it was transcendent, sometimes it was a mess, but almost never was it the same two nights running.

Jazz beyond Cream: Afrobeat and the long game

If you stop at Cream, you miss why Baker was so adamant about being a jazz musician. Writers have pointed out that to really understand him you have to follow him into his work with Fela Kuti, his own jazz trios and quartets and his late period band Jazz Confusion, where the rock hits barely register next to the improvising tradition he lived in. A survey of his post Cream career makes it clear that, seen from that angle, Cream looks like one explosive chapter in a long jazz story, not the other way around.

He even built a studio in Lagos, immersed himself in West African drumming culture and carried those patterns back into everything he played. Long before the term world music was fashionable, Baker was living in the overlap between bebop, African groove and British blues, treating genre lines as a nuisance rather than a rulebook.

Freedom, volume and the cost of playing without a net

Late in life, Baker summed up his philosophy bluntly: he had been playing jazz since he started, and he loved it because there was more freedom and more enjoyment when each player pushed and encouraged the others, creating what he called a very healthy situation. In one late interview about his passion for jazz he stressed that this was the mindset he brought into Cream, even when the audience just heard noise and feedback.

Of course, the reality inside that band was anything but healthy. The same freedom that let them stretch a song into something new also magnified ego, volume and rivalry, especially between Baker and Bruce. What Baker thought of as open, jazz style conversation often sounded to Clapton like three men trying to outgun each other, and the result was as exhausting as it was groundbreaking.

Was Cream really jazz, or something stranger

So was Baker right when he said it was all jazz. Strictly speaking, no. Cream still leaned on blues structures, rock song forms and riff based writing, and very few jazz bands were dragging twenty foot stacks on stage. You will not mistake a Cream album for a Blue Note session, or Baker’s résumé for that of a straight ahead bebop player.

But if you focus on method rather than label, his claim looks less outrageous. The harmonic movement is simple, yet the improvisation is open ended. The rhythm section does not behave like a rock foundation, it behaves like a volatile jazz engine. In that sense Cream sit at a weird crossroads, pointing toward jazz rock fusion, jam bands and even prog long before those tags hardened.

What drummers and listeners can steal from Ginger Baker

Baker’s personality was often toxic, but his musical lessons are gold. Drummers who only hear the bombast are missing the point.

- Study jazz and African drummers first, then worry about rock chops. Baker’s power came from deep rhythmic vocabulary, not from hitting harder.

- Treat the kit as a melodic instrument. build phrases on toms and cymbals that tell a story instead of recycling stock fills.

- Think like an improviser, not a metronome. react to the bass and guitar lines in real time, even inside simple song forms.

- Use dynamics as a weapon. some of Cream’s heaviest moments work because Baker drops the volume to a whisper before slamming back in.

- Embrace risk. not every Cream solo works, but the willingness to fall on your face is exactly what makes the great ones dangerous and alive.

Conclusion: jazz heart, blues face

When Ginger Baker snarled that all his wild drumming in Cream was jazz, not drugs or rock, he was doing more than defending his reputation. He was pointing back to a lifetime spent inside jazz clubs, record piles and African drum circles that just happened to explode into the mainstream for a few short years.

Hear Cream through that lens and the band stops being a relic of the psychedelic boom and starts to feel like a volatile experiment in mixing straight ahead jazz instincts with straight ahead blues fire. Whether you agree with Baker’s verdict or not, one thing is hard to deny: in that collision, a whole new kind of music really did evolve.