It’s the spring of 1966, and you step into EMI Studios on Abbey Road. The air is thick with cigarette smoke, and an assistant engineer carefully splices a piece of tape on a reel-to-reel machine.

Over in the corner, Paul McCartney is feeding a loop of recorded orchestral sounds into a tape deck, experimenting with something no pop band has ever tried before. In the control room, producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick are pushing the studio’s technology to its limits.

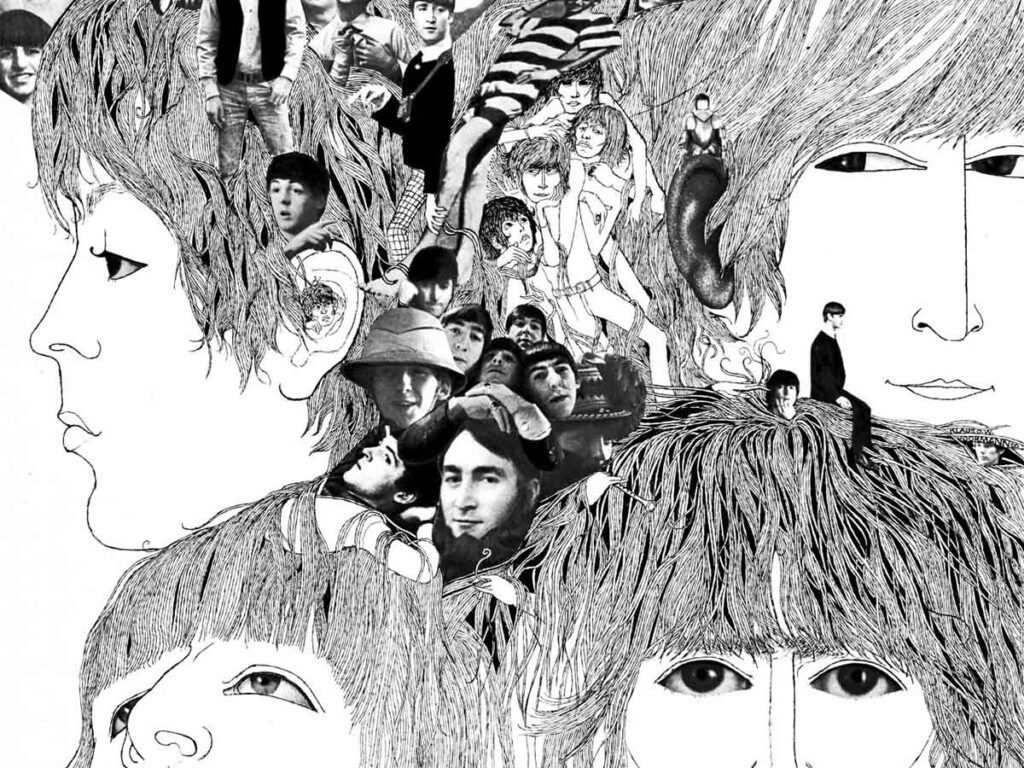

The Beatles are no longer just a rock band—they are sonic architects, about to create Revolver, one of the most groundbreaking albums in history.

Breaking the Rules: A New Approach to Recording

By 1966, The Beatles had grown tired of the constraints of live performance. Screaming fans made their concerts nearly impossible to hear, and the band was eager to explore new creative territory in the studio.

With Revolver, they decided to use the recording process itself as an instrument. Geoff Emerick, who had recently taken over as the band’s primary engineer, described how the group wanted to break new ground and move beyond conventional recording techniques.

The sessions, which began in April 1966, were filled with experimentation. John Lennon’s fascination with avant-garde techniques led to the use of tape loops, reverse recordings, and unconventional microphone placements. Paul McCartney, inspired by classical composers and avant-garde artists, pushed for richer textures and orchestral arrangements.

George Harrison explored Indian music more deeply than ever before, introducing the sitar and droning tonal structures to Western pop. And Ringo Starr, often underrated as an innovator, experimented with dampened drum sounds that would redefine rock drumming.

The Sound of the Future: Tape Loops and Backward Solos

One of the most revolutionary aspects of Revolver was its use of tape loops. McCartney had been fascinated by musique concrète—an experimental form of music that manipulated recorded sounds.

He began crafting loops at home, splicing together fragments of orchestral instruments, distorted voices, and random noises. These loops would later find their way into Tomorrow Never Knows, the album’s mind-bending closing track.

To achieve Lennon’s vision for the song, his vocals were processed through a rotating Leslie speaker, giving them an eerie, disembodied quality. Meanwhile, Harrison’s I’m Only Sleeping featured one of the earliest recorded backward guitar solos, painstakingly assembled by flipping the tape and recording the melody in reverse.

Listen closely to I’m Only Sleeping, and you’ll notice the guitar sounds almost liquid, bending and morphing in ways that feel otherworldly. Each note appears to swell in reverse, giving the song its dreamlike quality. The effect was so intricate that it took hours to get just right, with Harrison meticulously playing the melody backward so it would sound coherent when flipped.

Innovation at Every Turn

The album’s experimental spirit extended beyond just effects. For Eleanor Rigby, McCartney and Martin opted for a stark, cinematic string arrangement with no traditional rock instruments at all. Martin later described how the song’s arrangement was inspired by dramatic film scores, giving it a hauntingly modern sound that set a new standard for pop orchestration.

Even Yellow Submarine, often dismissed as a children’s song, featured cutting-edge sound effects. The band and studio staff created underwater noises by blowing bubbles into a bucket, layering them with studio chatter and distant echoes to create a surreal atmosphere.

Listen carefully, and you’ll catch snippets of laughter, spoken word phrases, and unusual clanking noises buried in the mix, giving the track its playful, almost hallucinogenic feel.

A Farewell to the Past, a Leap into the Future

By the time the Revolver sessions ended in June 1966, The Beatles had fundamentally changed the way albums were made. It was the beginning of their transition from pop stars to true studio innovators, setting the stage for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band the following year.

Emerick later reflected that working on Revolver felt like being part of a creative revolution, where every session brought new discoveries in sound and technique.

Revolver’s Enduring Legacy

Revolver wasn’t just an album—it was a revolution. With its groundbreaking use of studio technology, fearless experimentation, and genre-defying compositions, it redefined what pop music could be. More than 50 years later, it remains a benchmark of creativity, proof that sometimes, turning the world upside down is the only way to move forward.