On a cold New York night, John Lennon stepped out of a limo outside the Dakota with a cassette in his pocket. It held the final mix of Yoko Ono’s new single, “Walking On Thin Ice”, built around his searing last guitar solo and the sound he called their “new direction”. Just hours earlier he had given a hopeful radio interview about his future, his family and the comeback album that was finally putting his name back on the charts.

By midnight he was dead on the sidewalk, shot outside the building where he and Yoko had spent their most complicated, strangely domestic year. To understand those last 12 months in New York is to walk a tightrope between myth and something far messier: numerology and PR, open marriage ghosts, creative rebirth and the sense that Lennon was trying to rewrite his own story in real time.

The househusband in the Dakota: bread, babies and withdrawal

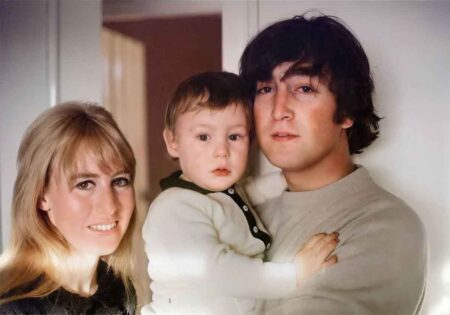

By the late 1970s Lennon had done something almost no rock star of his stature dared to do: he disappeared. From 1975 he largely walked away from the record business, choosing instead to stay in New York with Yoko and their son Sean, raising the boy and shutting the studio door. Years later he would point to the song “Watching The Wheels” as his answer to everyone who thought he was crazy for stepping off the merry-go-round.

In his final long interview with David Sheff, Lennon almost boasted about the domestic grind. “I’ve been baking bread,” he said when asked what he had been doing, before describing himself as a full-time “housemother” obsessing over nap times, baths and how his son swam “like a fish” because he personally took him to the Y. He talked about photographing his first loaf of bread like it was a new album and grumbling that there was no gold record for changing nappies.

Behind that homely image there was calculation as well as genuine pride. Biographers and friends alike note that Lennon felt he had missed his first son Julian’s childhood and was determined not to repeat the mistake, even if it meant trading stadiums for school runs and a quiet life inside the fortress-like Dakota building. For millions of fans, that “contented househusband” story became the default lens on his last years.

An unconventional marriage that never fully closed

The problem is that almost nobody close to John and Yoko describes their marriage as simple or serene. In the early 1970s, when things between them were raw, Yoko effectively selected a young assistant, May Pang, and told her she was going to become John’s lover while Ono pursued a relationship of her own. Pang recalls Ono insisting “you’re perfect” even as Pang begged her to pick someone else, and later telling John, “I fixed it for you”.

That “Lost Weekend” lasted 18 months and, according to Pang, never entirely ended. She says that even after Lennon moved back into the Dakota with Yoko, the two of them continued to see each other and remained lovers up to the winter of 1980, and that John’s later portrayal of those years as pure domestic bliss with Yoko was a carefully constructed image built to sell the reunion album Double Fantasy. Whether you take Pang at her word or not, her account makes Lennon’s public script about tidy monogamy feel like, at minimum, an edited version of the truth.

Other writers have gone further. Robert Rosen’s book Nowhere Man: The Final Days of John Lennon, based on his disputed recollections of Lennon’s private diaries, discards the bread-baking myth almost entirely and paints a darker picture: an artist obsessed with money, dabbling in the occult, wrestling with drugs and religion and trapped in a solitary struggle inside the Dakota even as he inched back toward the studio. Critics have called Rosen’s portrait controversial and sometimes salacious, but it has ensured that nobody can talk about Lennon’s last years without acknowledging the possibility of a much more tormented inner life.

A year in fast-forward: 1979-1980 at a glance

Key moments in New York and beyond

| Time | Where | What was happening |

|---|---|---|

| 1975-79 | The Dakota, NYC | Lennon retreats from the music industry, raises Sean, while Yoko manages business and art projects out of downstairs offices. |

| June 1980 | Atlantic to Bermuda | Six-day sailing trip through a violent storm jolts Lennon’s creativity back to life. |

| Summer 1980 | Bermuda & New York | He writes and demos the songs that will become Double Fantasy and the posthumous Milk and Honey. |

| Aug-Oct 1980 | The Hit Factory, NYC | Secret sessions with a handpicked band record Double Fantasy and a stack of extra tracks. |

| Nov 1980 | Global | Double Fantasy is released to mixed reviews; the single “(Just Like) Starting Over” climbs the charts. |

| 8 Dec 1980 | The Dakota & Record Plant | Last photo shoot, last radio interview, final mixing session for “Walking On Thin Ice” and Lennon’s murder outside his home. |

Bermuda: a storm, a disco and the return of the muse

Six months before he died, Lennon did something impulsive and almost reckless: he signed on as crew for a 43-foot sailboat heading from Newport, Rhode Island, to Bermuda. Somewhere in the mid-Atlantic the weather turned vicious, the crew were incapacitated with seasickness and Lennon, the supposed retired rock star, took the helm through the storm, emerging elated and strangely purified. In later interviews he said that when the skies finally cleared, “all these songs came” after five years of creative drought.

That Bermuda stay became a secret writing camp. With an acoustic guitar and a couple of boomboxes, he sketched out the bones of songs like “Woman”, “Beautiful Boy”, “I’m Losing You” and “Dear Yoko”, mailing cassettes back to Yoko in New York as the two effectively wrote their comeback album long-distance. The trip even gave the record its title: Double Fantasy was the name of a flower Lennon saw in the Bermuda Botanical Gardens, a tiny private joke about a couple trying to rebuild themselves.

The most notorious musical spark came one night in a Bermuda club, when Lennon heard the B-52s’ “Rock Lobster” on the dancefloor. He thought the shrieking, playful vocals sounded exactly like Yoko’s neglected avant-garde records and took it as a sign that the world might finally be ready for their brand of pop-art weirdness. “It’s time to get out the old axe and wake the wife up,” he later joked, citing the song as a main catalyst for returning to the studio.

Inside the Hit Factory: numerology, secrecy and a grown-up love album

Back in New York, Lennon and Ono quietly hired producer Jack Douglas and assembled a seasoned studio band: Earl Slick and Hugh McCracken on guitars, Tony Levin on bass, Andy Newmark on drums, George Small on keys. Sessions began at the Hit Factory in early August 1980 and were kept so secret that musicians used a private elevator and were initially not told whose record they were cutting. The plan was ambitious: record not just one album but enough material for a follow up, later released as Milk and Honey.

How that band was chosen was pure Yoko. According to Douglas’s team, every musician had to submit their birthdate so Ono could run their astrological and numerological charts, and at least a few candidates were quietly dropped for having the wrong sign. It sounded eccentric, but it fit the pattern: people who passed her numbers test gained access to the Dakota and to John.

Journalist David Sheff found that out the hard way. When he lobbied for a Playboy cover interview with the couple, Ono’s assistant phoned to ask his exact time and place of birth, because, as Sheff later wrote, that was how Yoko made many life and business decisions. Only after his horoscope checked out did she invite him to New York, where he spent three weeks embedded in their lives, following them to the studio, strolling Central Park and watching the couple hold hands like teenagers.

Musically, Double Fantasy was Lennon’s most nakedly autobiographical record since the early 70s, but without the primal-scream rage. Songs like “Watching The Wheels” and “Beautiful Boy” framed him as the contented ex-star and hands-on father, while “Woman” and “Dear Yoko” played like love letters to the woman who had pulled him out of the Beatles and, he believed, saved his life. Ono’s songs, interleaved track by track, were often more anxious and confrontational, hinting at paranoia, infidelity and the strain of celebrity marriage in a way that cut against the cosy narrative.

Press, perception and the art of myth-making

Once the record was in the can, Lennon and Ono went to work on something they understood better than almost anyone: image management. The three-week Playboy interview with Sheff was designed in part to rehabilitate Yoko, foregrounding her role as conceptual artist, political thinker and co-writer of “Imagine” rather than the cartoon villain who broke up the Beatles. Sheff later said Lennon was “adamant” that the feature focus on Ono, desperate for the world to see what he saw in her.

The strategy has only intensified over time. In his recent biography Yoko, Sheff argues that Ono, not Lennon, suffered most from their union, describing how an already established avant-garde composer whose work predated the Beatles found her career derailed and her art dismissed once she became “John’s wife”. The book highlights her influence on Lennon’s activism, his experiments in therapy and his late music, culminating decades later in her finally receiving official co-writing credit on “Imagine”.

Visually, too, they etched their own ending. On the morning of 8 December 1980, photographer Annie Leibovitz arrived at the Dakota tasked with shooting Lennon alone for a Rolling Stone cover. He refused unless Yoko was included, ultimately stripping naked and curling around her fully clothed body on the bed in an image he said captured their relationship perfectly. When that photograph hit newsstands weeks later, after his murder, it instantly became the defining portrait of their union: vulnerable John clinging to unreadable Yoko, the love story frozen at the moment before everything shattered.

The final New York day: hope, tape boxes and gunshots

The last day of Lennon’s life felt, perversely, like the happy payoff to all that work. In the afternoon he and Yoko sat for a long, upbeat interview with the RKO Radio Network, talking about Double Fantasy, middle age, and how excited he was to be creating again. He spoke about future projects and the simple pleasure of walking around New York without being mobbed, a luxury he had never enjoyed in Beatlemania Britain.

That evening they headed to the Record Plant to continue working on Ono’s “Walking On Thin Ice”, the edgy disco-influenced track that had become John’s obsession. The song featured his jagged guitar solo and a lyric about skating over danger that both of them, chillingly, described as prophetic. When they finally left the studio late that night, Lennon was literally carrying a tape box with the latest mix in his hands.

Outside the Dakota a small clutch of fans waited, among them a heavyset man with a copy of Double Fantasy who had already asked for an autograph earlier in the day. Lennon walked past him once more, this time into a hail of bullets at point blank range. The cassette of their new direction fell onto the blood-slicked pavement, and with it the chance to see where this strange, numerology-guided, Bermuda-born second act might have gone.

Aftermath: love story or cautionary tale?

In the decades since, the last year of John Lennon’s life has been polished into a kind of rock parable: the angry young Beatle finds peace as a househusband, discovers his muse again, reconciles with his great love and is killed just as he is about to step back on stage. There is truth in that arc. Friends and family recall a man more present as a father and less intoxicated by fame, and Yoko’s later work keeping his legacy alive has been relentless.

But the fuller story is more jagged and, perhaps, more human. Behind the bread and babies were carefully managed interviews, lovers who never quite left the frame, occult consultations about who was allowed into the room and at least one set of diaries that, if you believe Robert Rosen, reveal a man far less at ease than “Watching The Wheels” suggests.

For listeners, that tension only makes the music of those final New York months hit harder. Double Fantasy stops being a soft-focus comeback and starts to sound like what it really was: a risky, late attempt by two flawed, intertwined artists to tell the truth about their lives in public, just as time ran out.