Some love songs whisper. “Layla” doesn’t whisper at all; it screams, sobs and then drifts off into a dream.

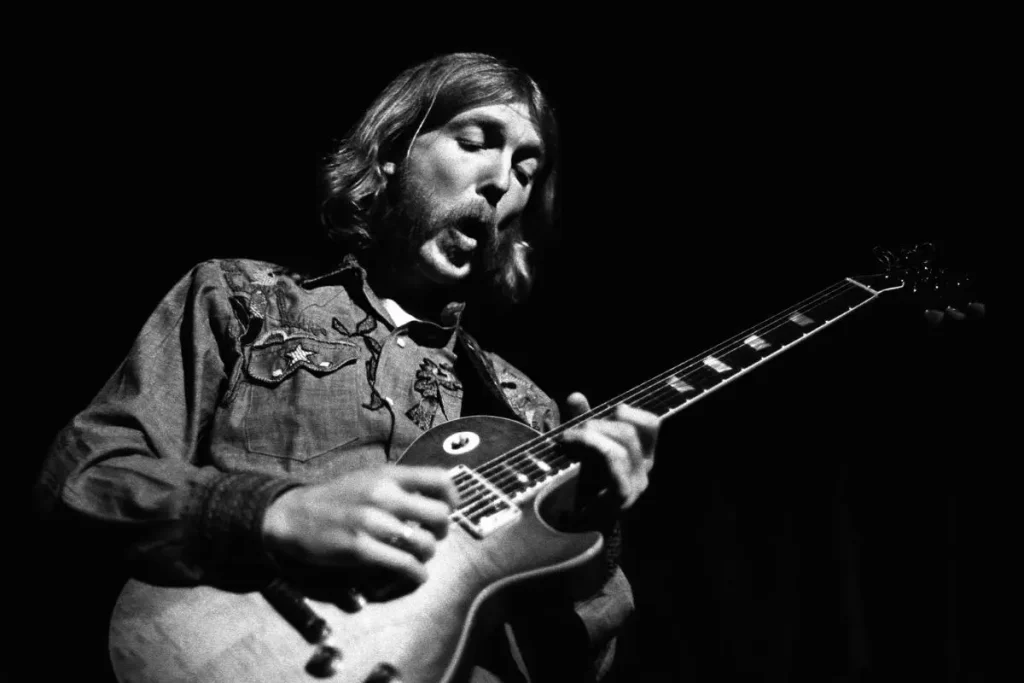

Eric Clapton may have written it as a confession of obsession over Pattie Boyd, but the record that came out of Criteria Studios is something stranger: a blues-soaked epic reshaped by Duane Allman, a 24-year-old jazz junkie from Macon whose ears were full of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and the darkest corners of the blues.

Duane Allman’s “spiritual battery” playlist

In a 1970 interview with Jon Tiven of New Haven Rock Press, Duane Allman was asked what he actually listened to. He shrugged off radio and reading music, saying he learned by ear and kept going back to the same records: early Miles Davis, Coltrane and pre-war and Chicago blues killers.

“I listen to Miles Davis (early Miles) and John Coltrane and Robert Johnson, Junior Wells, Muddy Waters; see, you get a goal in mind, a note that you want to hit with your band and then you gotta go out on the road and your spiritual battery runs down. You get home and you listen to that stuff and say ‘Ah, there it is, I have it before me, I know what to do’ and you go out and do it.”

That “spiritual battery” line is the key. For Allman, records were not background noise; they were fuel. He was treating Miles and Coltrane the way hard-core jazz players treat them, as manuals in phrasing, time and tension, then re-aiming that knowledge at loud Marshall stacks and long Southern nights, as he later described in a now-famous quote.

Jazz, blues and a Southern-rock mind

Decades later, saxophonist and critic Robert Palmer recalled Allman telling him that his long, lyrical solos came directly from listening to Miles and Coltrane, especially the album Kind of Blue, which he said he had played almost exclusively for years. You can hear that influence in the way Duane rides a vamp, stretching time instead of just running licks, as explored in this reflection on his jazz influence.

Band insiders have also pointed to Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” and Miles’s “All Blues” as touchstones for the Allman Brothers Band’s modal jams, especially “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” where Duane’s solos move in waves over just a few chords rather than dutifully chasing every change. That approach is straight out of the Miles-and-Trane playbook, smuggled into a supposedly “boogie” band.

From Muscle Shoals to Macon: the sound Duane brought to “Layla”

Before anyone outside the South knew his name, Allman was the secret weapon of FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, setting Wilson Pickett’s “Hey Jude” on fire and cutting slide parts for Aretha, King Curtis and Boz Scaggs. He favored a ’57 Gibson Les Paul Goldtop and an SG through roaring Marshall stacks live, but the real magic was his Coricidin-bottle slide, which gave him a vocal, human wail that fused Delta blues with something far more expansive.

Out of that studio grind came the Allman Brothers Band, the group that effectively invented 1970s Southern rock by welding blues changes, country melodies and jazz-informed improvisation into marathon pieces like “Dreams,” “Statesboro Blues” and “Whipping Post.” Their live album At Fillmore East proved extended jams could be muscular, harmonically adventurous and brutally emotional all at once.

Writers have noted that while At Fillmore East may be Allman’s purest legacy, it was the opening seven notes of “Layla” that turned him into a rock icon: one blast of slide in open tuning from a glass pill bottle, and every guitarist on earth suddenly knew his name, as captured in this look at his life and legacy.

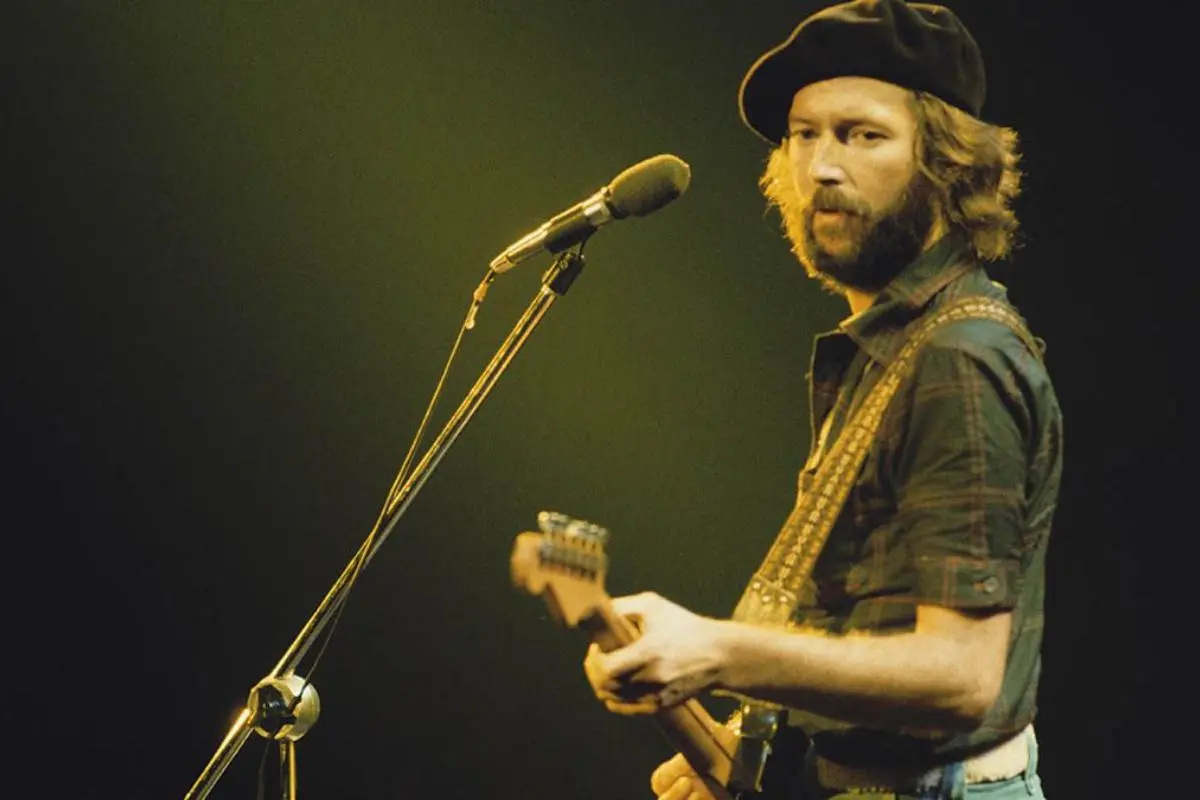

Crashing Clapton’s love song

Allman did not even head to Miami planning to play. He went down to Criteria Studios just to watch Clapton’s new band make a record, because, as he told Tiven, he had admired Eric’s playing for years and wanted to see “the cat” with a real group around him, a story he recounted in that same interview with Jon Tiven. Instead, Clapton greeted him like an old friend, insisted he plug in, and what was supposed to be a guest spot on one or two tracks turned into Duane playing all over the album.

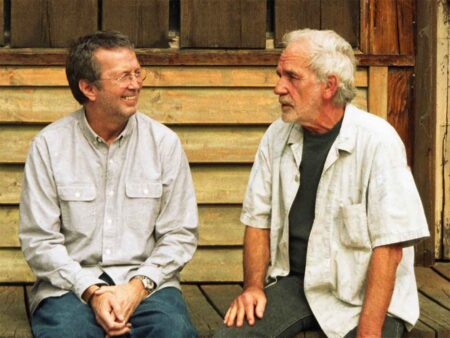

Producer Tom Dowd had already seen the Allmans blow the roof off venues and, sensing that the Derek and the Dominos sessions were bogging down, dragged Clapton to a Miami Beach show. Clapton was floored, later calling Duane the “musical brother that I never had” and naming Allman’s solo on Wilson Pickett’s “Hey Jude” as his favorite guitar solo of all time, as detailed in this piece on Allman’s isolated “Layla” guitar track. Once Duane walked into Criteria with a Les Paul and a slide, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs suddenly had a second lead guitarist and a second musical brain.

Inside the “Layla” sessions: six guitars and a stolen blues cry

Clapton has been open about how drastically Allman changed “Layla.” He started with a ballad about his hopeless love for Boyd, inspired by the Persian story of Layla and Majnun, but says he knew the song still needed a motif. That motif arrived when Allman came up with the now-famous riff, which Clapton has admitted was “pretty much a direct lift” from Albert King’s “As the Years Go Passing By” on the Stax album Born Under a Bad Sign, compressing a slow vocal plea about having “nothing I can do” if a lover walks out into a 12-note electric scream, as explored in this breakdown of the “Layla” riff.

In a 1985 Guitar Player interview, Clapton broke down just how dense the first section of “Layla” is: 16 tracks in all, with six guitar tracks. There is one rhythm part from Eric, three more tracks of him harmonizing with himself on the main riff, a track of Duane’s solos, and another track where the two guitarists double each other’s signature licks; both reportedly plugged into the same little Fender Champ amplifier, Clapton likely on a Strat and Allman on the now-mythic ’57 Goldtop that later fetched about $1.25 million at auction, according to this detailed account of the sessions.

| Track | Who | Role in the mix |

|---|---|---|

| Rhythm guitar | Clapton | Chugs under verses and choruses, gluing the song together |

| Main riff harmonies (3 tracks) | Clapton | Stacks the opening riff in power chords and harmonized lines |

| Lead/slide solos | Allman | Fretted verse fills and searing slide, especially in the outro |

| Shared signature licks | Allman & Clapton | Doubled phrases that give the riff its huge, two-octave punch |

At the end of the song, Allman stacks slide lines into what one writer dubbed a “bottleneck symphony,” finishing with those eerie, high bird-call sounds that still raise hair on the back of your neck, as remembered in this vintage Guitar Player article. Allman later pointed out that Clapton played some slide on the track too, but said you can tell them apart by tone: Eric’s Fender is thinner and sparkling, while Duane’s Gibson is thicker and closer to a scream.

Producer Tom Dowd, who had worked with everyone from Coltrane to Ray Charles, said the sessions felt like watching two guitarists share a single brain, describing Clapton and Allman reacting to each other’s ideas so quickly it seemed like telepathy as they layered those six intertwined parts, something you can hear clearly in isolated “Layla” guitar tracks.

Stealing like a jazz musician

The delicious irony is that this most famous of rock riffs is, by Clapton’s own account, a straight lift from a slow Stax blues. But Allman and Clapton treat Albert King’s vocal line the way jazz players treat a standard: they quote it, twist the melody, speed it up and answer it with harmony guitars and slide.

That is exactly what Duane was talking about in his “spiritual battery” comment. You do not copy records to become a jukebox; you live with them until the feeling behind a phrase is so clear in your mind that you can aim your own band at that emotional target and hit it in your own accent. In “Layla,” the ghost of a Stax vocal, the modal lessons of Miles and Trane, and the howl of Delta blues all show up in one riff.

What guitar players can actually take from Duane

1. Wear out the right records

Allman was not binging random playlists; he was obsessing over a small canon: Kind of Blue, Coltrane’s modal work, Robert Johnson, Junior Wells, Muddy Waters, records he discussed both in Palmer’s essay and in that New Haven Rock Press interview. If you want that depth, pick a handful of records and listen until you can sing every solo from memory.

2. Think like a horn section, not a lone gun

On “Layla,” Allman is not just shredding over Clapton; he is answering, shadowing and doubling like a horn section built out of two guitars. That mindset came straight from listening to Miles’s bands and Coltrane’s quartets, where lines weave in and out rather than sit on top.

3. Use long vamps to tell long stories

Allman Brothers epics such as “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” and “Whipping Post” work because the harmony sits still long enough for a soloist to build a narrative rather than race chord changes every bar, a hallmark of their Southern-rock approach that also echoes the modal feel described in analyses of “Layla”. You can hear the same instinct in Duane’s “Layla” soloing: he is not just running boxes, he is pacing a story over a groove.

4. Make slide a voice, not a gimmick

Duane’s Coricidin-bottle slide tone is so vocal that you almost forget there is no singer during parts of “Layla,” and that is why it still cuts, a quality also celebrated in that 1981 Guitar Player tribute. If your slide playing sounds like a special effect, you are missing the point; chase phrasing, vibrato and dynamics the way a great singer does.

Charging your own spiritual battery

You can argue about who “owns” “Layla,” but here is the uncomfortable truth for Clapton fans: without Duane Allman, it would probably have remained a very good ballad. With him, it became a nervous breakdown on tape, framed by a stolen Albert King line, hammered into shape by six guitar tracks and lit up by a kid who spent his nights with Miles and Coltrane.

Allman did not live long enough to see how completely guitar players would fetishize every note he recorded, but he left a clear blueprint. Get your ears right, feed your spiritual battery with the heaviest records you can find, and then have the nerve to walk into the studio, lift what you love and turn it into something dangerous and your own.