In 1968, rock guitarist Eric Clapton found himself at a crossroads. As Cream—his explosive power trio with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker—raced toward its implosion, Clapton heard an album that would shake his musical foundation. That album was Music from Big Pink by a group simply called The Band. It stopped him in his tracks.

The Band’s sound, a rootsy, unflashy blend of blues, country, R&B, and early rock, stood in stark contrast to the bombast of the psychedelic era. For Clapton, it was a wake-up call. As he later reflected, hearing their music made him feel he was “in the wrong place with the wrong people doing the wrong thing.” Cream’s improvisational clashes and ego-fueled dynamic suddenly felt out of step with what Clapton now saw as the future: authenticity, subtlety, and songs that felt lived-in.

And he wasn’t the only one. In the midst of a cultural moment defined by rebellion, The Band offered a different kind of revolution—one rooted in tradition, family, and feeling.

Contents

A New Sound from Old Souls

Released in July 1968, Music from Big Pink was a strange, gentle arrival. Its creators—four Canadians and one Arkansan—had spent years on the road as the Hawks, backing up rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins and later Bob Dylan during his controversial electric tours. By the time they decamped to a pink house in upstate New York, they were already seasoned players.

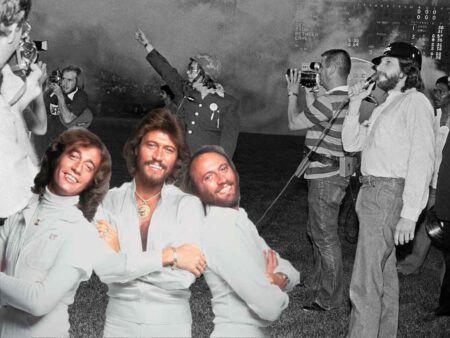

Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel, Rick Danko, and Garth Hudson didn’t look like rock stars, and they didn’t try to. On the album’s inner sleeve, they posed not with psychedelia or fashion-forward flair—but with their parents and extended family. It was a quiet statement: this music wasn’t about spectacle. It was about home.

Musically, the album drew from deep wells: gospel harmonies, Appalachian folk, Delta blues. Tracks like “Tears of Rage” and “The Weight” didn’t shout—they whispered, grooved, and reflected. Critics called it rustic. Artists like George Harrison and Elvis Costello later cited it as pivotal. But it was Eric Clapton who took action.

Clapton’s Turning Point

At the time, Clapton was the poster child for virtuosity. Cream had just released Wheels of Fire, filled with extended solos and explosive improvisations. But Music from Big Pink cast a long shadow. Clapton, by his own admission, was disillusioned with Cream’s direction—frustrated by infighting, exhausted by the constant need to outplay everyone.

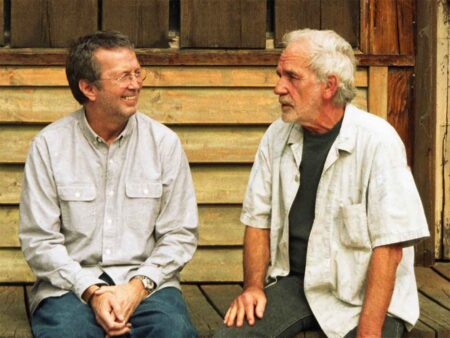

In interviews and his autobiography, Clapton described his reaction to The Band’s music as an awakening. It wasn’t just about sound—it was about purpose. Their understated interplay and democratic spirit were the antithesis of the flash-and-fury ethos he’d been living in. Though the exact quote varies over time, he consistently recalled thinking something to the effect of, “I’m in the wrong place with the wrong people doing the wrong thing.”

Not long after, Clapton began stepping back. He sought collaborations that felt more grounded—eventually forming Derek and the Dominos, where ensemble spirit took precedence over guitar heroics. He even briefly entertained the idea of joining The Band themselves.

The Band’s Quiet Rebellion

Robbie Robertson later described The Band’s approach as “rebelling against the rebellion.” While other groups were burning flags or turning amps to 11, The Band found meaning in restraint and connection. Their lyrics evoked the Civil War, backwoods rituals, and front porch storytelling.

By grounding themselves in Americana—despite most of them being Canadian—they helped ignite a wave of roots rock that would shape the early ’70s. Neil Young, The Grateful Dead, Van Morrison, and even The Rolling Stones took note. Their sound wasn’t nostalgic—it was a reinvention of what rock could be when it looked backward to move forward.

And their impact wasn’t just musical. The Band made sincerity fashionable again. In a landscape of swirling colors and chaos, they offered sepia tones and soul.

The Aftershock

Cream officially disbanded in late 1968, with Clapton confirming the split that July. While tensions in the band had been simmering for some time, Music from Big Pink helped clarify for Clapton what he no longer wanted: spectacle over substance, solos over songs.

In the years that followed, Clapton pursued projects with Delaney & Bonnie, Blind Faith, and later his solo career—all bearing traces of The Band’s influence in tone, texture, and collaborative spirit. He even recorded his own version of “The Weight” with Aretha Franklin in 1970, further cementing the song’s place in the post-psychedelic canon.

The Band, meanwhile, continued to release landmark records like The Band (1969) and Stage Fright (1970), culminating in The Last Waltz—a farewell concert and film that became one of the most revered music documentaries of all time.

Something Deeper Than Cool

Looking back, it’s not just the music of The Band that explains their enduring impact. It’s what they represented. They didn’t reject innovation—they redirected it. They didn’t deny the power of rock—they reminded it where it came from.

For Eric Clapton, hearing Music from Big Pink was like catching a glimpse of the road he’d forgotten he was trying to find. And for listeners still discovering that record today, the same feeling remains. No pyrotechnics. No pretense. Just groove, grit, and grace.