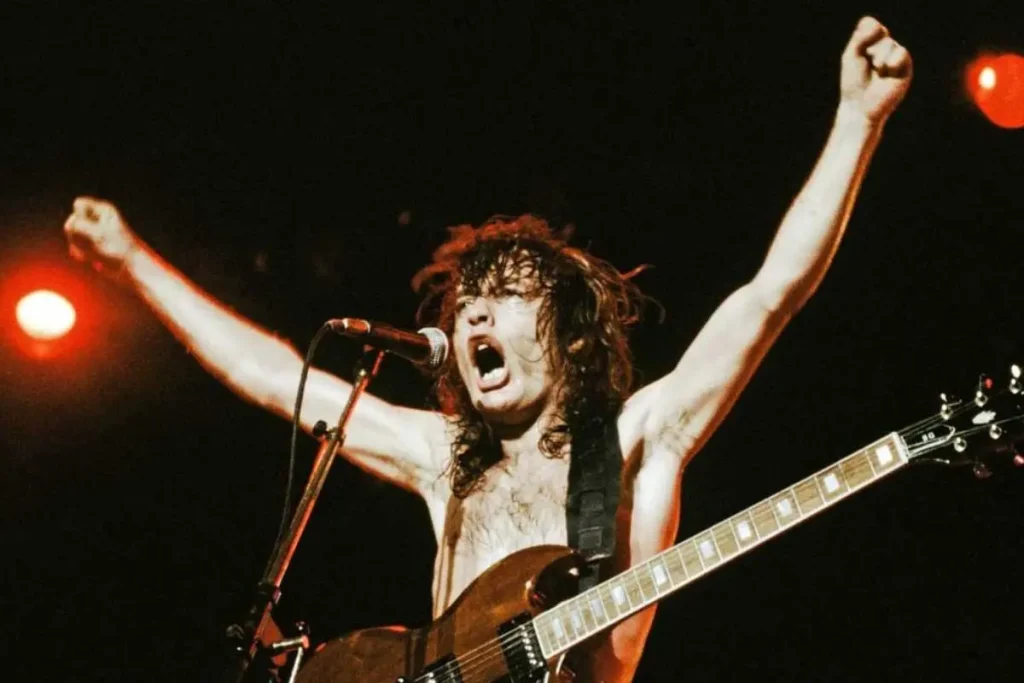

Angus Young is proof that rock does not need permission to be sophisticated. With AC/DC, he helped reduce the genre to its most dangerous essentials: a riff you can’t escape, a backbeat that hits like a mallet, and a lead guitar that sounds like it is laughing at the rules while obeying them perfectly.

He was born in Scotland and raised in Australia, then somehow became the most famous “schoolboy” in music history. Decades on, the uniform is still not a gimmick so much as a warning label: this show will be loud, fast, and unreasonably joyful.

From Scotland to Sydney: the immigrant engine behind the noise

Angus McKinnon Young was born in Glasgow, Scotland, and later moved with his family to Australia. That dual identity matters because AC/DC never sounded like a purely British or purely Australian rock band; they sounded like outsiders crashing every party and somehow becoming the house band.

The basics of Young’s early life and the band’s origin story are well documented: Angus and his older brother Malcolm co-founded AC/DC in 1973, building their reputation the old way, by being undeniable onstage night after night. It is the rare “origin myth” that is not marketing spin but simply the same story retold by different witnesses: the band hit hard, and Angus hit harder.

The schoolboy uniform: branding, rebellion, and a practical stage weapon

Plenty of rock stars wore costumes, but few created an icon. Angus’s schoolboy outfit works because it flips power dynamics: the “kid” becomes the most commanding figure in the room, while the adults in the crowd scream like teenagers.

The story of how the uniform became his signature has been widely discussed in Australian media, including recollections tied to the band’s early years – especially the origin of the schoolboy-uniform idea. The key point is that it started as a look and became a character, giving Angus permission to be extra physical, extra manic, and extra fearless under the lights.

“I’m sick to death of people saying we’ve made 11 albums that sound exactly the same. In fact, we’ve made 12 albums that sound exactly the same.” – Angus Young

That quote gets repeated because it lands a deeper truth: AC/DC’s sameness is not laziness, it is discipline. Angus uses that discipline to make tiny changes feel seismic, like turning the same steering wheel a fraction and still ending up in a ditch on purpose.

Why the Gibson SG became Angus’s Excalibur

Angus Young and the Gibson SG are one of rock’s great permanent pairings. The SG’s thin body, easy upper-fret access, and raw midrange punch suit a player who lives in the space between rhythm and lead, where riffs turn into solos without warning.

Even when gear talk gets obsessive, Angus’s setup has always been more practical than mystical: a reliable guitar, a loud amp, and hands that do the rest. If you want to understand why an SG is such a common choice for hard rock, Gibson’s serial-number and dating resources show how standardized, workhorse production models can become lifelong tools for working musicians.

Angus’s real “secret”: the right hand and the pocket

Here is the provocative claim that upsets some guitar forums: Angus Young is not primarily a “lead guitarist.” He is a rhythm guitarist with a lead vocabulary, and that is why his solos feel inevitable rather than decorative.

Listen closely and you will hear a near-constant conversation between his picking hand and the drummer’s groove. The notes are often simple; the timing is not. That is also why he can make a two-note bend feel like a plot twist.

The Malcolm factor: the most underrated partnership in hard rock

Angus gets the spotlight, but Malcolm Young built the engine room. Their partnership created a perfect division of labor: Malcolm’s tight, percussive rhythm framework made Angus’s flash sound even wilder, because the floor never moved.

AC/DC’s story is often sold as “simple rock,” but the band’s real trick is structural. The songs are stripped down, yet arranged with the care of classic pop: clear hooks, uncluttered parts, and dynamics that build without changing the formula. The band’s official updates have continued to present AC/DC as an active legacy, underscoring how central that identity still is to their narrative.

Solos that feel like fights: how Angus makes melody aggressive

Angus’s best solos are not technical showcases. They are little street brawls with melody, built from blues language, pentatonic muscle memory, and a sense of escalation that never loses the beat.

He favors phrases that sing, then repeats them with slight variations until the crowd is trapped in the chant. That is not an accident – it is crowd psychology. He is composing in real time, but he is also conducting.

Three Angus trademarks you can hear in minutes

- Call-and-response phrasing – a short “question” lick answered by a sharper “reply.”

- Big, vocal bends – wide bends that land cleanly, like a human voice pushing past comfort.

- Rhythmic insistence – repeated motifs that lock to the groove instead of floating over it.

“Highway to Hell” and “Back in Black”: riffs that became public property

Some riffs stop belonging to a band and start belonging to the world. “Highway to Hell” is one of them: a hard-rock singalong that sounds like rebellion but functions like folk music, passed from arena to arena with zero loss of meaning.

Then there is “Back in Black,” the comeback statement that turned tragedy into a monument. The title track’s riff is practically a lesson in negative space: it leaves room for the drums to punch and for the vocal to strut, while Angus’s guitar fills the gaps like a predator circling. Angus’s place among rock’s giants is reinforced by major “greatest guitarist” canon, which treats this kind of durability as a true form of influence.

Stagecraft as athletic event: the duckwalk, the sprint, the controlled chaos

Angus’s performance style is a masterclass in committing to the bit. The duckwalk nods to Chuck Berry, but in Angus’s hands it becomes something more feral: less “showbiz,” more “charging bull that learned choreography.”

What looks like chaos is actually pacing. He builds tension by moving, by teasing the front rows, by stretching a solo just long enough to make the next chorus hit like a release valve.

What modern guitarists can learn from Angus (without copying him)

- Write parts, not licks – your solo should feel like part of the song’s architecture.

- Play fewer notes, mean them more – conviction beats complexity in a loud band.

- Make the groove sacred – if the pocket collapses, everything else is theatre.

How the industry rates Angus: canonization (and why it’s still arguable)

Angus Young has been canonized by the rock press, often appearing in major “greatest guitarist” lists that reward influence and signature as much as technique. Even a concise overview of AC/DC’s profile in mainstream music databases reflects how the band’s status – and Angus’s role in it – has remained fixed in the culture for decades, as shown by long-running artist histories and summaries.

But here is the spicy counterpoint: the lists only capture half the story. Angus is not important because he is “one of the best.” He is important because he made a specific version of rock guitar so durable that it outlived trends, fashion cycles, and entire subgenres that tried to replace it.

What Angus’s career says about rock itself

Angus Young represents rock’s most stubborn argument: that simplicity can be a form of authority. In a music culture that often equates progress with more, Angus doubled down on less and made it feel bigger than life.

There is also a cultural point worth noting: AC/DC’s catalog has been managed and preserved as major publishing property, reflecting its continued global demand across media and performance contexts. The band’s publishing partnership is a reminder that this music is not nostalgia – it is still valuable, active repertoire.

A quick listening guide: hear Angus like a musician, not a fan

If you want to truly “get” Angus, do not start by chasing his tone. Start by listening to how he places notes against the rhythm section, especially where the guitar seems to push ahead but never breaks the band’s stride.

| Track | What to listen for | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| “Highway to Hell” | Riff spacing and chorus lift | Proof that restraint can be an anthem |

| “Back in Black” | Negative space and syncopation | A riff that teaches groove |

| Any extended live solo | Motif repetition and escalation | How to build drama without shredding |

Myths, misunderstandings, and what’s actually true

Myth: “Angus is just blues licks.” Reality: He uses blues vocabulary, but his real skill is arranging it into hooks that work at stadium volume.

Myth: “AC/DC songs are all the same.” Reality: The band uses a consistent template, but the best tracks have distinct feels, tempos, and riffs that are instantly recognizable even without vocals.

Myth: “It’s all gear.” Reality: Angus’s sound is hands-first, and the gear is simply sturdy enough to survive the punishment.

Conclusion: the loudest lesson Angus Young ever taught

Angus Young’s legacy is not merely that he played iconic solos in a schoolboy uniform. It is that he turned rock guitar into a physical language: direct, unpretentious, and impossible to ignore when done with total commitment.

In a world where music is often optimized for algorithms and quiet backgrounds, Angus remains the patron saint of the opposite idea: plug in, turn up, and make the room deal with you.