Bruce Springsteen has written about cars, Catholic guilt, and the American hangover better than most novelists. But the most convincing love story in his universe may be the one he never scripted: the friendship with saxophonist Clarence “The Big Man” Clemons.

Their relationship was part music, part comedy duo, part social experiment, and part street-level theology. Onstage, Springsteen narrated the dream, and Clemons made it sound like the dream could actually win.

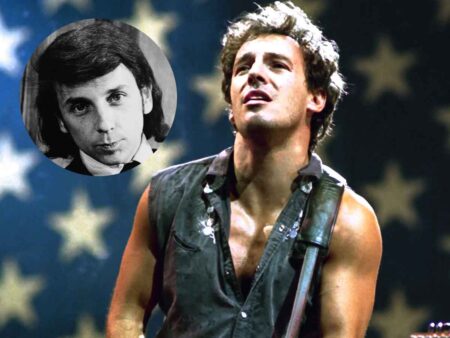

A stormy origin story that became gospel

Every great band has a “how we met” tale, but Springsteen and Clemons have an origin myth that plays like a comic book: rain, thunder, a crowded Jersey club, and a larger-than-life stranger demanding a chance to blow. The official Springsteen camp even admits the details have been embroidered, then shrugs as if to say: the truth is the feeling.

On Springsteen’s own site, Clemons’ biography frames that meeting at the Student Prince as “the stuff of legend” and treats the accuracy as almost irrelevant, because the impact was immediate: the moment the Big Man arrived, the band “found its soul.” It also traces Clemons’ sound back to R&B sax royalty (notably King Curtis and Junior Walker), which helps explain why his entrance always felt like a doorway from rock into church.

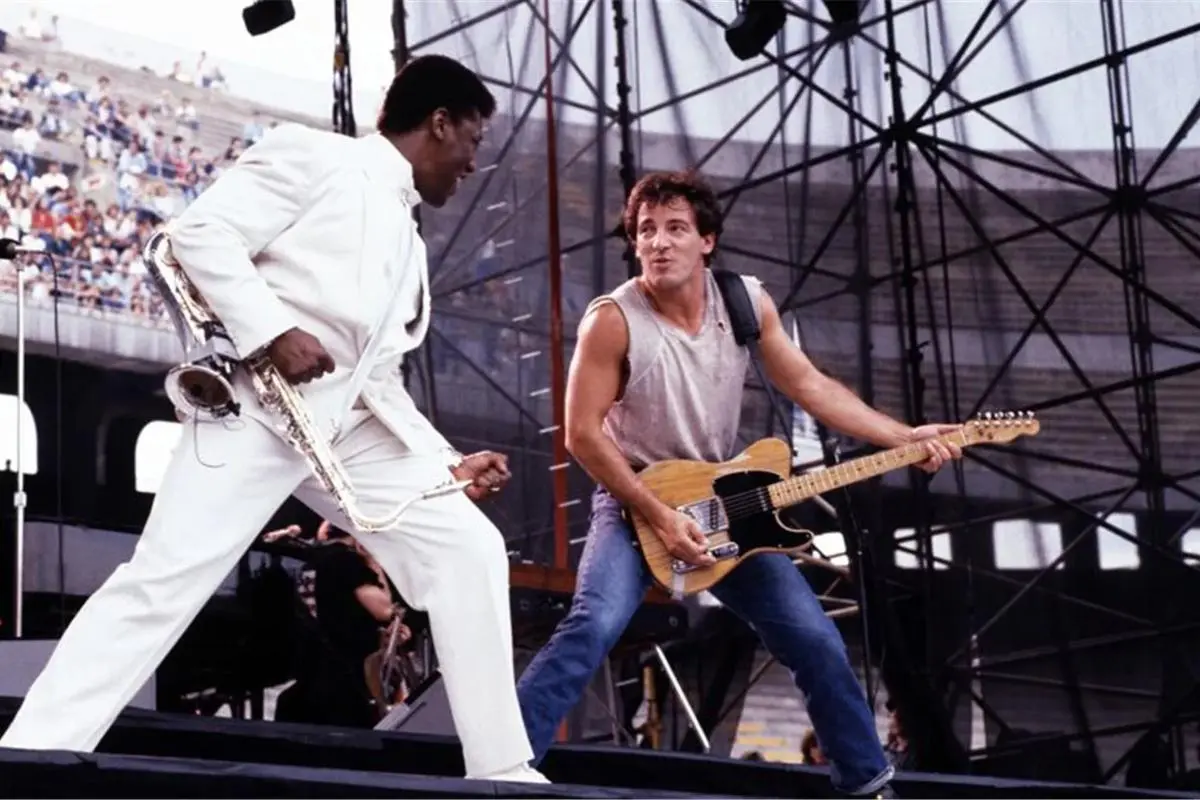

Clarence wasn’t a sideman: the E Street Band had two frontmen

Most rock frontmen treat the horn section like stage dressing: you bring them out for color, tuck them back into the shadows, and keep the spotlight on the singer. Springsteen did the opposite, building an arena-sized narrative that required a second hero to make the story believable.

That second hero was Clemons, and the “relationship” wasn’t just personal. It was structural: Springsteen wrote like a filmmaker, and Clemons played like the camera that refuses to cut away.

| Springsteen’s role | Clemons’ role | What it created |

|---|---|---|

| Storyteller and ringleader | Witness and enforcer | A band that felt like a neighborhood, not a brand |

| Wordy, restless verses | Big melodic “answers” | Call-and-response drama (like soul music in leather) |

| Control of pacing | Permission to explode | Solos that felt like plot twists, not decoration |

The sax as narrator (not a gimmick)

Clemons’ genius in the Springsteen context wasn’t just tone or chops. It was narrative timing: he often waited like a boxer in the corner, then hit the song at the moment the lyrics ran out of oxygen.

If you’re listening with musician ears, the “Big Man magic” is usually one of three moves: a long, held note that changes the emotional temperature, a simple hook that the crowd can sing back, or a solo that feels like a second verse spoken without words. That’s not virtuoso showing off; it’s arranging in real time.

Springsteen admitted it: he leaned on Clarence

Fans love to romanticize the partnership, but Springsteen himself put it in blunt, almost embarrassing terms. In his eulogy for Clemons, he describes a photo of them together and openly admits he “leaned on Clarence a lot,” even joking that he made “a career” out of it.

The same eulogy lands on the real point: Clemons was the “love light” in the room, and Springsteen felt lucky to stand near that kind of force “in the Temple of Soul.” It’s a rare public confession from a famously private writer: this wasn’t just my sax player; this was my safety, my ballast, and my proof of what the music was supposed to mean in Springsteen’s eulogy for Clarence Clemons.

The kiss, the scandal, and the point everyone missed

Yes, we have to talk about the onstage kiss, because it wasn’t a throwaway gag. In a Rolling Stone interview, Springsteen seems genuinely amused by all the theorizing around it, insisting he never felt self-conscious about it and that the truth is simpler: “We were just close,” and their bond was one of the deepest relationships of his life in his interview about touring with the E Street Band.

Clemons was even more direct, describing the connection as love and a space where two “strong” men could drop the armor and feel trust without turning it into a sexual performance. In an Associated Press profile, he frames it as passion without sex, a public act of respect that most rock culture pretends not to need, as described in TheGrio’s profile of Clemons. That’s why it mattered: it broke the rules of macho rock in front of the exact audience that expected those rules.

Born to Run’s cover: the handshake that became a billboard

The relationship didn’t just live onstage. It got printed, framed, and shoved into every record store window in America: Springsteen leaning on Clemons on the cover of Born to Run.

The Bruce Springsteen Archives calls the image culturally weighty, pointing out how the stark black-and-white composition and the split-front-and-back design elevate Clemons from “sideman” to co-star; their curatorial note on the Eric Meola photo makes clear how the design turns the cover into a statement. In a genre that often erased the band behind the singer, this cover basically says: the story is two men, not one.

The cover was also a dare

It’s tempting to treat that sleeve as “just iconic,” but there’s a sharper edge under the nostalgia. Reporting on Peter Ames Carlin’s book Tonight in Jungleland, People describes Springsteen pushing for Clemons to be featured not only because of friendship, but also as a statement against racism in a tense era.

Carlin also recounts an incident where bandmates faced racist hostility at the Jersey Shore, and the experience helped harden Springsteen’s sense that the image should be openly interracial and openly united—context included in People’s reporting on why Clarence was on the Born to Run cover. In other words: the cover wasn’t merely affectionate. It was meant to irritate the right people.

When the E Street marriage cracked

Real relationships have fractures, and theirs wasn’t immune. The E Street Band breakup hit Clemons like a family split, and accounts from his memoir capture the shock as physical, not theoretical.

A Rolling Stone tribute quotes Clemons describing the moment Springsteen told him the band was ending: he went quiet, stopped smiling, and even the people around him could see he’d been emotionally leveled—recounted in Rolling Stone India’s tribute to Clarence Clemons. That reaction is the hidden truth behind the legend: if Clemons was Springsteen’s co-star, the “off” switch was never going to feel like a normal business decision.

What musicians can steal from the Boss-Big Man blueprint

If you lead a band, the Springsteen-Clemons relationship is a masterclass in how to build something bigger than a setlist. It’s also a reminder that “chemistry” is often the result of deliberate choices, repeated until they feel like fate.

For bandleaders

- Cast a foil, not a backup. Give one player permission to be a character, not a utility.

- Write with negative space. Leave gaps where another voice can answer, argue, or lift the song.

- Share the myth. A band becomes a culture when the audience can name the people inside it.

For sax players (and any featured soloist)

- Make one note matter. Big impact often comes from conviction and timing, not complexity.

- Build hooks, not just solos. Give crowds something they can hum on the way out.

- Play the role. Sometimes you are the romance, sometimes the threat, sometimes the priest.

After the Big Man: grief, tape, and the unreplaceable tone

When Clemons died, Springsteen didn’t talk like a boss who lost an employee. He talked like a man whose weather changed, later saying losing Clemons was “like losing the rain,” and describing how hearing Clarence’s sax part could still crack him open.

One report details Springsteen visiting Clemons at his bedside and later breaking down when Clemons’ sax filled the room on a studio track, with producers even pulling a live performance part into the recording. That’s the final proof of the relationship: even in absence, Clemons remained the sound of “home” inside Springsteen’s music, as recalled in Springsteen’s “like losing the rain” interview.

Conclusion

Springsteen and Clemons are remembered as a rock duo, but their real achievement is weirder and more daring: they made male friendship look epic, theatrical, and unashamed. They made tenderness feel tough.

And musically, they did something almost unfair to every bar band that came after them. They proved that one saxophone, placed in exactly the right relationship with exactly the right songwriter, can turn rock and roll into soul.